5 Reasons Only Paul Thomas Anderson Could’ve Adapted Thomas Pynchon’s Inherent Vice

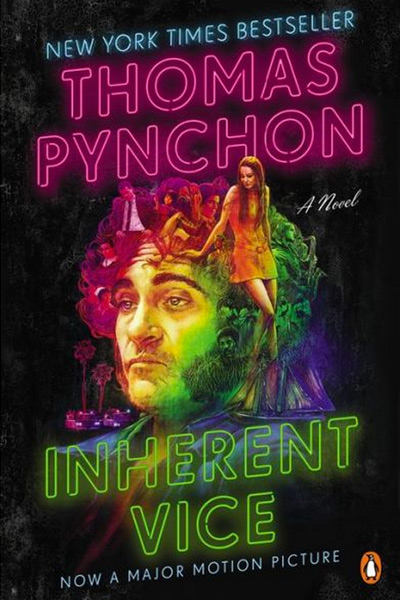

The novels of Thomas Pynchon have generally been considered unfilmable. Dense, chaotic, cerebral—Pynchon’s oeuvre is composed of novels that don’t lend themselves readily to cinematic moments and the condensation required to turn a book into a two-hour (or even three-hour) film. In 2009, however, the odds shifted a bit when Pynchon published Inherent Vice, one of his most accessible and “mainstream” novels ever—and indeed, the film adaptation is being released on December 12 (as the sardonic voiceover in the trailer notes, “just in time for Christmas”).

The novels of Thomas Pynchon have generally been considered unfilmable. Dense, chaotic, cerebral—Pynchon’s oeuvre is composed of novels that don’t lend themselves readily to cinematic moments and the condensation required to turn a book into a two-hour (or even three-hour) film. In 2009, however, the odds shifted a bit when Pynchon published Inherent Vice, one of his most accessible and “mainstream” novels ever—and indeed, the film adaptation is being released on December 12 (as the sardonic voiceover in the trailer notes, “just in time for Christmas”).

The film was written and directed by Paul Thomas Anderson, known for Boogie Nights, Magnolia, There Will be Blood, and The Master. As is often the case with Pynchon’s novels, the revelation of this one fact—Anderson as the writer/director of Inherent Vice—makes everything else click into better focus. Because there is no one else in the world better equipped to write and direct this film. Here’s why.

Anderson is the Film World’s Pynchon

Pynchon writes novels that tell complex and often confounding stories with dense layers of meaning and twisting, unpredictable plots that reward frequent rereads and the occasional bout of research. Anderson creates films that tell complex and often confounding stories with dense layers of meaning and twisting, unpredictable plots that reward frequent rewatching and the occasional bout of analysis. If there’s another director out there more suited to take on Pynchon, I’d like to hear it.

He’s Used to Stories with a Lot of Characters

A Pynchon novel is crowded with a cast of characters that are equal parts mysterious, amusing, and frustrating—just like the crowded films Anderson tends to make. The crowded tableaus of Boogie Nights and Magnolia and even the relatively sparsely populated The Master mark Anderson as one of the few Hollywood directors capable of managing Pynchon’s sprawling list of supporting and minor characters, all of whom have significance requiring careful attention no matter how little they appear on screen.

He Tells Stories that Don’t Make Sense at First. Or at Second.

People have been reading and discussing Pynchon’s novels for decades now. Inherent Vice is certainly one of the most accessible of Pynchon’s novels, but it remains more challenging than most books. Anderson’s films have inspired a similar level of discussion, from the meaning of the number 82 referenced throughout Magnolia, to whether or not the Master actually spoke in Freddie’s dream, to what the push-in on the tiny note declaring “but it did happen” meant, again in Magnolia. Anderson is used to weaving clues and thoughtful references into his films, making him the ideal choice to work with someone of Pynchon’s complexity.

Anderson’s Other Works Explores the Concept of ‛Inherent Vice’

The phrase “inherent vice” only appears in one other Pynchon novel, but its meaning is thematically explored in both Pynchon’s novels and Anderson’s films. The phrase means the unavoidable flaw in anything that is often unnoticed at first but which dooms everything to eventual ruin and destruction, no matter how nobly conceived or carefully constructed. One layer of the book explores the last gasp of California’s underground drug culture as it sours into the 1970s, and Anderson’s films often tell a story of a golden age descending into madness and chaos.

Anderson’s Good at Sprawl

Anderson’s films all have the feel of an epic, even if the stories they tell are small on the surface. The same could be said of Pynchon, who often takes small-scale plot (such as a woman trying to settle an ex-lover’s estate) and sprawls it out into a huge adventure covering plenty of geographic and conceptual ideas. The eccentric detective story of Inherent Vice seems like the plot of an Anderson movie that just hadn’t been made yet, except of course now it has and that is possibly the most Pynchonesque/Anderson-like thing to ever happen.

In the end, if you’ve been curious about Pynchon but intimidated by the scale and complexity of his work, Inherent Vice might be the perfect place for you to start. Yes, some of Pynchon’s older works are shorter—but this book has the most conventional structure and storytelling in Pynchon’s oeuvre, making it the Pynchon gateway drug (which is appropriate, given the book’s setting in the closing days of the southern California drug scene’s Golden Age). But if you’re going to watch the film first, you can rest assured the perfect director will be working with the material.