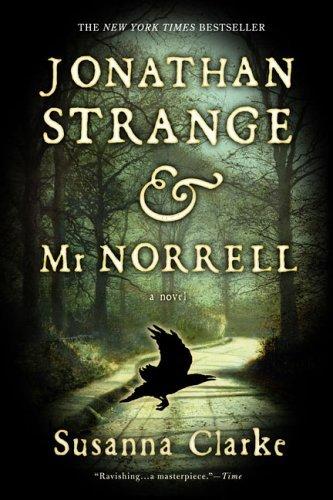

6 Books for People Who Loved Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell

Susanna Clarke’s fantasy masterpiece Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell is 900 pages long, but if you’re like me, even that wasn’t enough time spent in the gorgeous, witty landscape of a magical Napoleonic-era England. Not even her follow-up short story collection, The Ladies of Grace Adieu, could hope to satisfy my thirst for More Of That, Please.

Susanna Clarke’s fantasy masterpiece Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell is 900 pages long, but if you’re like me, even that wasn’t enough time spent in the gorgeous, witty landscape of a magical Napoleonic-era England. Not even her follow-up short story collection, The Ladies of Grace Adieu, could hope to satisfy my thirst for More Of That, Please.

Happily, the BBC agreed with me, and graciously filmed a miniseries based on Clarke’s novel. The first clip was released this week, with the series rumored to air as soon as January. My resulting (completely undignified) excitement not only immediately kicked off my umpteenth reread, it got me thinking about other books that might tide me over until the miniseries debuts. The problem is, there are so many reasons to love this novel, and so many books it will make you want to read.

If you can’t get enough of that perfect British observational wit…

Clarke’s prose owes a debt to Jane Austen, a master of tone and character development. However, another writer from the same era is as strong a match: William Makepeace Thackeray, particularly in his greatest novel, Vanity Fair. Lovers of Clarke’s assured, witty narrative will find similar enjoyment in Thackeray’s penetrating pronouncements on many of the same societal foibles Clarke takes on (minus the magicians, plus a lot more social climbers). Like Clarke, who sends up the archetypes of classic British novels, Thackeray does a first-rate job skewering the selfishness of his characters and, by extension, any readers who might side with them. If you love Clarke for her bewitching prose and brutally honest character analysis, Thackery is a safe bet.

If you loved it for the magical alternate history…

You’re in luck. Clarke’s novel is part of what has become a burgeoning genre. One great example of the trend is Naomi Novik’s Temeraire series, which follow the exploits of a company of dragon-riders who have formed a sort of early 19th-century RAF, battling it out with their French counterparts for control of the air. Like Clarke, Novik introduces real myth and magic into the England of the era and shows how they might affect a society at war.

Sorcery and Cecelia, Or The Enchanted Chocolate Pot, by Patricia C. Wrede and Caroline Stevermer, also treads similar territory. It’s a charming coming-of-age tale in which two Proper Young Ladies of Regency Society suddenly encounter a hidden magic in different corners of England, and, of course, hijinks (and handsome beaux) shortly ensue. Written in epistolary style (in letters the authors actually sent to one another, developing the plot along the way), the story follows half of the title pair enjoying the society of London while the other stays at their country estate. It’s a short read, with an irresistible premise and a delightfully lighthearted tone.

If you can’t resist wartime drama and romance…

Then look no further than Georgette Heyer’s An Infamous Army. Heyer is best known as a grande dame of Regency romance, and the first half of this novel exemplifies the type of farcical comedy of manners for which she is best known, featuring an Independent Lady and Dashing, Impossible Gentleman negotiating their love affair through ballrooms dances and morning calls. That’s until Napoleon and his Hundred Days throw a wrench into the fizzy marriage plot, and very quickly, a farce is transformed into a wartime epic, complete with one of the best-researched depictions of the Battle of Waterloo I have ever encountered (the hero’s role is fiction, but not much else is).

If you were stoked every time the Gentleman with the Thistledown Hair appeared…

Though Clarke’s magical world is a foreboding place, the Gothic atmosphere of her menacing take on the world of Faerie weaves a strong spell over many readers. In the Gormenghast novels, Mervyn Peake adopts a similar attitude. He explores the castle of Gormenghast, a labyrinthine building in an increasingly advanced state of decay. Much like in Clarke’s Faerie, full of growing malice, the reader moves through the corridors of the castle, encountering a series of surreal mini-worlds populated by characters that are the stuff of grotesque childhood fears and very adult disappointments. Peake’s creation, both a caution to his readers about the temptations of fetishizing melancholy and an acknowledgement of its fascination, should satisfy readers who want to spend even more time exploring the overgrown realms of Faerie.

If you loved it for all those footnotes and Regency celebrity cameos…

Then please let me recommend David King’s fantastic Vienna, 1814: How the Conquerors of Napoleon Made Love, War, and Peace at the Congress of Vienna. King writes the best kind of page-turning, novelistic narrative history, taking us backstage at the conference that attempted to put Europe back in order at the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars to explore the social whirl of the kings, ministers, courtesans, princelings, and pageboys attending or lurking around the edges. King’s work illuminates the height of a political system in which all politics were personal and the fate of millions could be (and was) changed because the prime minIster of Austria was too busy pining for his mistress to focus properly, or because the mistress of one king threw better parties than the wife of another. Readers who adored Clarke’s delightful depiction of a crotchety Wellington or strangely affecting interlude with the mad King George III could not do better than to pick up King’s enthralling account of the Congress of Vienna.

Will you be watching Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell?