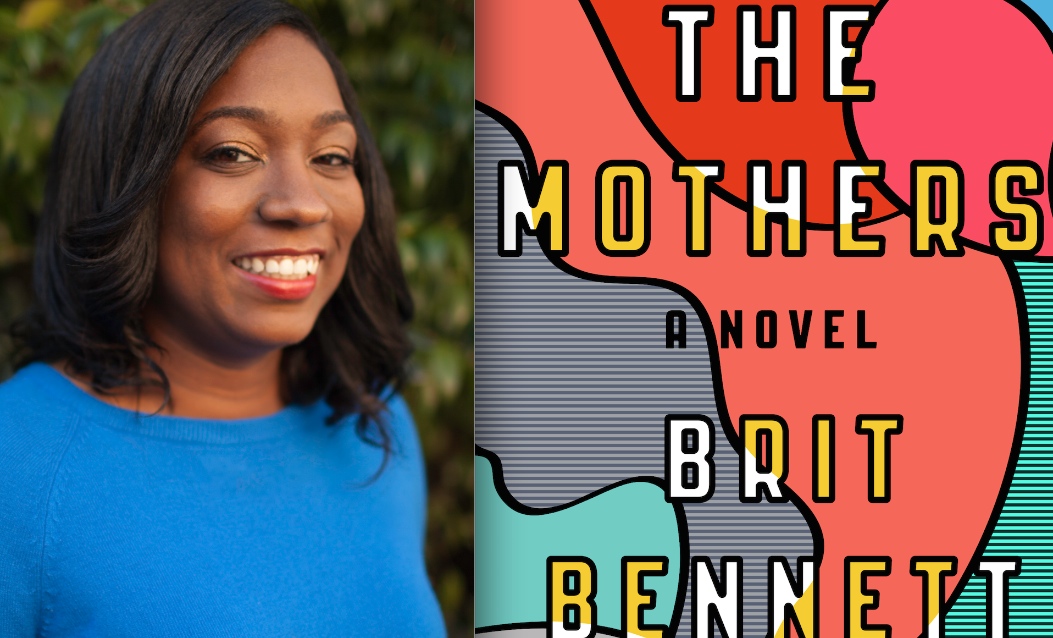

Brit Bennett: “Loss Keeps Circling”

As she tells it, the inspiration for Brit Bennett’s captivating debut novel, The Mothers, was her own uncertainty about where she fit in. “I grew up in the church but I always felt a little outside of it, particularly as a young person. I would see all of these kids my age who seemed so devout and solid in their belief. I’ve always wondered, “How are people so sure about anything?” I had a lot of doubts, but I thought that doubting was the opposite of believing, so I kept it to myself. I’m sure most of the kids I grew up with had their own doubts, but at the time I just thought, everyone else has it together except me. That’s where my interest in these young characters growing up in a conservative, gossipy, church community originated.”

Debug Notice: No product response from API

The Mothers traces the friendship between two young women, Nadia and Aubrey, who have lost their mothers in different ways, Nadia to suicide and Aubrey when her mother chooses her abusive husband over her children. But the novel moves far beyond the relationship of the girls, and the stifling religious community they grow up in, to question the very nature of grief. “Loss can feel shameful, which makes it so impossible to talk about, but it also pervades every aspect of your life,” Bennett explains. “I think all of the characters are bound by deep loss—whether the loss of a mother, or the loss of a child, or the loss of a certain type of future they hoped they’d live. As I’ve grown up alongside these characters, my interests expanded from simply “teenagers and their problems” to thinking about how their choices as adults, in response to loss, can affect their entire community. Originally I thought that loss would ease over time but now that book is finished, I think, you can be walking around 50 years later and see or smell something that can bring you right back. Loss keeps circling and we can never completely escape it.”

Bennett always wanted to be a writer, but until her undergraduate years, she felt alone in her passion. “I’d never met professional writers, so it seemed like an impossible career. And then suddenly I went to undergrad and I had independent studies with Stegner fellows. I was really fortunate to have mentors who took me seriously and worked with me on The Mothers for three years before I even got to grad school.

“One of my mentors was Amy Keller, and I showed a lot of the early drafts to her. She helped me with the psychological aspects of writing a book: how to get rid of my perfectionism and allow myself to make mistakes. The draft that I worked on with her I wrote out of order. I was anxious because I thought I was doing it wrong. She said, ‘Who says you have to write a book in chronological order?’

“Another mentor encouraged me to write multiple chapters from Luke’s mother’s perspective that never made it into the book, but allowed her character to, hopefully, become much more complex. It felt feeling freeing to do that and not worry, is this going towards my word count? Is this furthering the plot?”

The Mothers underwent many significant changes during the seven years Bennett worked on it. “I’m a pretty drastic reviser. I enter the revision process with the belief that anything is changeable, which I think is both a strength and a weakness. Because when you solve certain problems, you often create new ones, so I spent a lot of years putting out fires and sparking new ones that I had to respond to. Recently, I found an old flash drive from 2009 at my parents’ house and the thing that surprised me was that, despite all the characters and plots I cut, the first line of the book was exactly the same.”

Bennett drew inspiration from a variety of literary works, both classic and contemporary for inspiration, “A few of the standouts for me were Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche, Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin, Bastard out of Carolina by Dorothy Allison and Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward, which thematically has some similarities of impending motherhood in the wake of grieving a lost mother. Americanah was also very technically instructive as far as illustrating how to move through time — one of the hardest things for me to figure out in my own writing — in a coming-of-age narrative. I remember being impressed with how efficiently Adiche moved from childhood to adulthood for all of those characters.”

But, says Bennett “I always return to Toni Morrison—she’s one of the first authors who made me want to write a novel, and I’m in awe of what she can do with language. Her imagery is unforgettable, and she writes such strange, often unlikable characters who still have fully realized lives. I read The Bluest Eye in the beginning of high school and a lot of it went over my head. I don’t think that’s the right gateway novel to Toni Morrison when you’re fourteen, but, the fact that the book was so beguiling to me actually made me want to read her work more. I read Song of Solomon when I was studying abroad and that was a big influence, too. For the first time in my life, I wasn’t in America and I felt I had the space to really consider what it means to be an American. That book really centers on the idea of finding our ancestors.”

Though fiction has been her main passion, in 2014, in the wake of the Michael Brown and Eric Garner cases, Bennett felt called to write essays. “I was texting back and forth with a friend about how frustrated I was seeing the self-congratulatory social media posts of some of my white friends, while the the rest of my black friends were all grieving. There was such a gap in their responses. My friend said “Just write about it.” I thought, I don’t write nonfiction, I’m writing a novel. But, Jia Tolentino, who I was in grad school with, had been asking me for essays for Jezebel. I wrote the essay from an emotional space where I was wondering, ‘What’s the value of good intentions?’

“It was very jarring at first to take a break from a novel I’d been writing mostly on my own for years to work on essays where I would receive immediate feedback from readers within moments of publication. But I try to approach nonfiction writing the same way I approach fiction—with empathy, always asking big questions, always looking for interesting connections between ideas. And I was fortunate that Jia gave me the initial platform to do it, because, through that, my agent found me, which set the process of publishing The Mothers in motion.”

Now that The Mothers is finished, Bennett, has made peace with her past doubts. “I’ve come to realize that doubt is part of belief. Believing something wholesale with no room for doubt is like being a computer. There’s nothing real about it and it’s not how I want to move through the world. I make space for ambiguity. I’m not afraid of it anymore.”

The Mothers traces the friendship between two young women, Nadia and Aubrey, who have lost their mothers in different ways, Nadia to suicide and Aubrey when her mother chooses her abusive husband over her children. But the novel moves far beyond the relationship of the girls, and the stifling religious community they grow up in, to question the very nature of grief. “Loss can feel shameful, which makes it so impossible to talk about, but it also pervades every aspect of your life,” Bennett explains. “I think all of the characters are bound by deep loss—whether the loss of a mother, or the loss of a child, or the loss of a certain type of future they hoped they’d live. As I’ve grown up alongside these characters, my interests expanded from simply “teenagers and their problems” to thinking about how their choices as adults, in response to loss, can affect their entire community. Originally I thought that loss would ease over time but now that book is finished, I think, you can be walking around 50 years later and see or smell something that can bring you right back. Loss keeps circling and we can never completely escape it.”

Bennett always wanted to be a writer, but until her undergraduate years, she felt alone in her passion. “I’d never met professional writers, so it seemed like an impossible career. And then suddenly I went to undergrad and I had independent studies with Stegner fellows. I was really fortunate to have mentors who took me seriously and worked with me on The Mothers for three years before I even got to grad school.

“One of my mentors was Amy Keller, and I showed a lot of the early drafts to her. She helped me with the psychological aspects of writing a book: how to get rid of my perfectionism and allow myself to make mistakes. The draft that I worked on with her I wrote out of order. I was anxious because I thought I was doing it wrong. She said, ‘Who says you have to write a book in chronological order?’

“Another mentor encouraged me to write multiple chapters from Luke’s mother’s perspective that never made it into the book, but allowed her character to, hopefully, become much more complex. It felt feeling freeing to do that and not worry, is this going towards my word count? Is this furthering the plot?”

The Mothers underwent many significant changes during the seven years Bennett worked on it. “I’m a pretty drastic reviser. I enter the revision process with the belief that anything is changeable, which I think is both a strength and a weakness. Because when you solve certain problems, you often create new ones, so I spent a lot of years putting out fires and sparking new ones that I had to respond to. Recently, I found an old flash drive from 2009 at my parents’ house and the thing that surprised me was that, despite all the characters and plots I cut, the first line of the book was exactly the same.”

Bennett drew inspiration from a variety of literary works, both classic and contemporary for inspiration, “A few of the standouts for me were Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche, Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin, Bastard out of Carolina by Dorothy Allison and Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward, which thematically has some similarities of impending motherhood in the wake of grieving a lost mother. Americanah was also very technically instructive as far as illustrating how to move through time — one of the hardest things for me to figure out in my own writing — in a coming-of-age narrative. I remember being impressed with how efficiently Adiche moved from childhood to adulthood for all of those characters.”

But, says Bennett “I always return to Toni Morrison—she’s one of the first authors who made me want to write a novel, and I’m in awe of what she can do with language. Her imagery is unforgettable, and she writes such strange, often unlikable characters who still have fully realized lives. I read The Bluest Eye in the beginning of high school and a lot of it went over my head. I don’t think that’s the right gateway novel to Toni Morrison when you’re fourteen, but, the fact that the book was so beguiling to me actually made me want to read her work more. I read Song of Solomon when I was studying abroad and that was a big influence, too. For the first time in my life, I wasn’t in America and I felt I had the space to really consider what it means to be an American. That book really centers on the idea of finding our ancestors.”

Though fiction has been her main passion, in 2014, in the wake of the Michael Brown and Eric Garner cases, Bennett felt called to write essays. “I was texting back and forth with a friend about how frustrated I was seeing the self-congratulatory social media posts of some of my white friends, while the the rest of my black friends were all grieving. There was such a gap in their responses. My friend said “Just write about it.” I thought, I don’t write nonfiction, I’m writing a novel. But, Jia Tolentino, who I was in grad school with, had been asking me for essays for Jezebel. I wrote the essay from an emotional space where I was wondering, ‘What’s the value of good intentions?’

“It was very jarring at first to take a break from a novel I’d been writing mostly on my own for years to work on essays where I would receive immediate feedback from readers within moments of publication. But I try to approach nonfiction writing the same way I approach fiction—with empathy, always asking big questions, always looking for interesting connections between ideas. And I was fortunate that Jia gave me the initial platform to do it, because, through that, my agent found me, which set the process of publishing The Mothers in motion.”

Now that The Mothers is finished, Bennett, has made peace with her past doubts. “I’ve come to realize that doubt is part of belief. Believing something wholesale with no room for doubt is like being a computer. There’s nothing real about it and it’s not how I want to move through the world. I make space for ambiguity. I’m not afraid of it anymore.”