#CoverFlip Revisited: A Progress Report

In 2013, author and critic Maureen Johnson raised a searing point about the publishing industry: regardless of content, it tends to package books by men differently from books by women. Male authors are more likely to warrant strong fonts, bold colors, and imagery that commands Take me seriously. Novels by female authors, by contrast, are more likely to be dolled up, made to look frivolous in italics and pastels.

Literary fiction by women is, in other words, too often packaged in a lazy, reductive way that diminishes its impact.

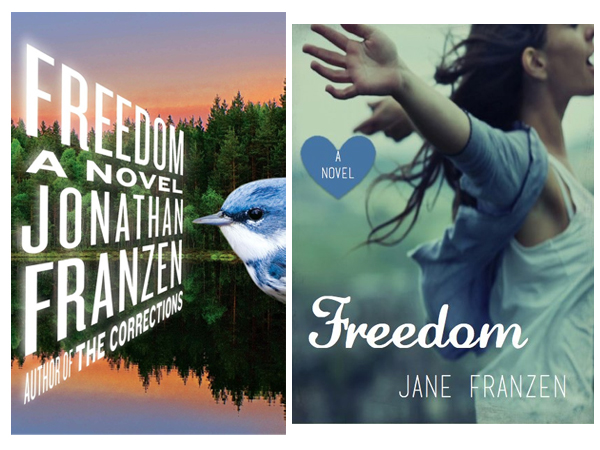

Johnson’s call to arms in response to her discovery, hashtagged #CoverFlip, became a pop cultural phenomenon, as people raced to mock up, for example, what Freedom would look like if it bore the name Jane Franzen instead of Jonathan.

At roughly the same time, photojournalist and author Deborah Copaken spoke out in the Nation about the sexism she experienced trying to publish her first book, a memoir about being a photojournalist in war zones:

Random House changes the book’s title to Shutterbabe, which a friend came up with. I beg for Shuttergirl instead, to reclaim at least “girl,” as Lena Dunham would so expertly do years later. Or what about Develop Stop Fix? Anything besides a title with the word “babe” in it.

I’m told I have no say in the matter. The cover that the publisher designs has a naked cartoon torso against a pink background with a camera covering the genitalia. I tell them it’s usually my eye behind the camera, not my vagina. I fight—hard—to change the cover. Thankfully, I win this one, agreeing to shoot the cover photo myself, gratis. When my publicist tries to pitch the book to NPR’s Terry Gross, a producer tells him that Terry likes the “Shutter” part of the title but not the “babe” part.

Now that the year is 2015, I’m wondering, what has changed? Anything? Did people in publishing get the message and are highbrow books by women books treated with more respect? To my surprise, I think the answer might be yes.

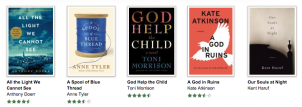

Consider this screenshot from the Barnes & Noble website, which helpfully juxtaposes novels by prize-winning authors of both genders, including Anthony Doerr’s All The Light We Cannot See, Toni Morrison’s God Help The Child, and Kate Atkinson’s A God In Ruins.

There’s no appreciable visual difference, to my eye, between the Doerr on the left and the Morrison and Atkinson in the middle. All offer strong fonts, bold colors, and eye-catching design, the kind that says, Don’t mess with me unless it’s to give me a medal.

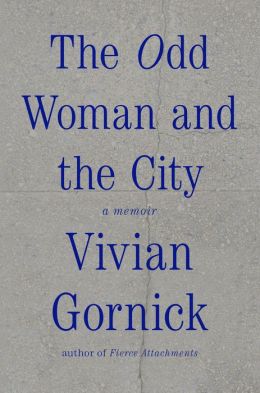

The new Vivian Gornick memoir has the words “woman” and “city” in the title, and yet there are no martini glasses or high-heeled shoes to be found on that stark and appropriate-looking cover.

Consider, too, Buzzfeed’s list of 2014’s best books by women. One or two of the covers may trade in stereotypical colors and images. For the most part, though, they are dressed to impress, packaged to look strong rather than pretty.

One-time bookseller Michele Filgate generally agrees with this assessment:

We have seen some great covers for women writers over the past couple of years. The Goldfinch, Dear Thief, and Nobody Is Ever Missing are three that come to mind. But we still have a long way to go.

She also offers a radical corrective: “This is going to sound sacrilegious, but part of me wishes we could do away with cover art. It would solve a lot of problems. Practically speaking, however, I know that’s not a good idea.”

Assuming we retain the tradition of cover art, some will continue to draw on lazy stereotypes and clip-art shorthand. And, of course, prestige fiction and memoir by women has often, though definitely not always, been given more consideration than the average lady-book. Still, just as H is for Hawk, P is for Progress. Let’s give publishers a P and keep on moving in what is mostly the right direction.