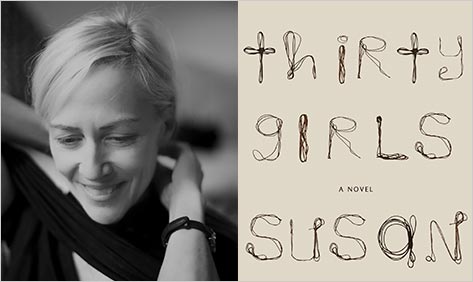

Everything That Lives Is Holy: Susan Minot on Thirty Girls

Susan Minot takes a radical departure in Thirty Girls, her first novel in twelve years. Definitively leaving behind the cultivated New England milieu of her earlier books, she explores a setting deep in the Ugandan bush where, in 1996, thirty teenaged girls were abducted from their school and forced to kill and function as sex slaves. Although far from her comfort zone, the book is a triumph of novelistic empathy and courageous risk-taking.

Throughout the interview in the corner of a cozy Greenwich Village hotel lobby, Ms. Minot attends to our questions with a concentrated seriousness of purpose, frequently broken by a radiant smile that warms the room. But we start small. — Daniel Asa Rose

The Barnes & Noble Review: What’s with the bandage on your index finger?

Susan Minot: I sliced off the tip last night peeling potatoes with a new peeler.

BNR: But you shouldn’t be peeling potatoes in the first place. All the nutrients are in the skin.

SM: But there’s still plenty in the potato itself.

BNR: I see you’re quite firm on this point.

SM: I suppose I am.

BNR: Then I concede. Let’s talk about your new book. It seems to me you have done a very brave thing on at least two levels. First, you’ve found an entirely new setting within which to reinvigorate yourself. And it certainly seems to have done the trick. The protagonist Jane repeatedly alludes to how “alert” Africa makes her, how revitalized she is to be “finding herself here” in a place where “each step seemed to take her deeper into a true life she had not known before.”

SM: Change and renewal are themes in life, aren’t they? We keep growing throughout life.

BNR: Yet no matter where you set your characters, they always seem to grapple with “desire and death” [8] as their perpetual subjects.

SM: Those themes are certainly always there. But they don’t have to be all-consuming. People can have a variety of concerns at the same time. Even those undergoing grave or traumatic experiences will acknowledge the need for lightness or even entertainment.

BNR: Well, that’s a second way your book is brave. You don’t address the tragedy of the African girls in a vacuum. There’s also a second plot about Jane falling in love with a younger African man as she comes closer and closer to her interview with Esther, one of the thirty girls.

SM: Why is that brave?

BNR: Because you open yourself to the charge of trivializing the third world horrors with first world concerns of love for an unavailable man that might be considered superficial, up against the bigger questions of abduction and rape.

SM: I don’t consider the first world concerns any less important than the third world ones. Matters of life and death are certainly more pressing in practical terms, but the fact that they are “bigger” or more dramatic does not necessarily make them more important in terms of conveying the experience of being alive. If we’re talking about struggling to be in your life, all concerns are valid….

BNR: Go on….

SM: Well, it’s what I sometimes find myself telling my students [at NYU]. I see them dismissing their day-to-day issues as petty or unworthy, because they are aware of their privilege. I try to point out to them that their experience and their point of view is what they have to offer in their writing, if they can succeed in bringing them out. “Everything that lives is holy.”

BNR: Is that the Catholic in you saying that?

SM: No, the poet. I’m quoting William Blake. But Tolstoy, too, is very eloquent in talking about how all suffering is the same. In War and Peace, Pierre has the credentials to address this issue when he’s on his grueling march to Moscow as a prisoner of war.

BNR: As a matter of fact, I think the clash between the two plots in your book creates an interesting dissonance, and also real-time suspense as Jane brings her concerns closer and closer to Esther’s. To be brutally honest, that’s when my initial worry as a reader was finally allayed.

SM: What initial worry?

BNR: That you might have chosen this topic strategically, to deepen your oeuvre with the instant gravitas a Big African Book can confer, a la Dave Eggers or Ishmael Beah.

SM: On the contrary, I always had the feeling that the topic sort of chose me.

BNR: I eventually came to that feeling myself. I was entirely won over by the way the two worlds inevitably collided around two thirds of the way through.

SM: More like three quarters, I’d say.

BNR: Luckily there’s more than enough honest stuff to keep us going until then. For one thing, there’s the painterly description of the landscape: “the side of the road crumbl[ing] like pie crust,” “a screen of haze infus[ing] the air with a silver light,” “puffs [rising] out of the trees like dialogue bubbles from villages hidden from sight…”

SM: I was going to be a painter, you know, and I still paint.

BNR: And for another thing, there’s the weighty love Jane has for Harry, who is a paraglider, of all weightless things.

SM: For five years the book was titled Flight.

BNR: So it went through more than one title. Was it a particularly difficult book to write?

SM: The most grueling of them all. It took me seven years. I thought it would take three.

BNR: What was grueling, exactly?

SM: Making Jane not simpering. Getting Esther’s voice right. I wasn’t sure I could pull it off, speaking in the voice of a young African girl.

BNR: But it has the ring of truth. Esther is so traumatized she’s in a semi-dissociative state, yet you capture it. “Maybe I’ll get up when I’m ready. Maybe I won’t. I hate everyone.” How did someone from such different circumstances ever manage to channel this semi-literate girl from the bush?

SM: I don’t know. Your doubts can sometimes spur you on, you know. And there’s an internal voice saying, “Come on. Do it, do it.”

BNR: As for the collision itself, when it finally does occur, it is enormously and thoroughly moving. I actually don’t think the book would have worked as well if we hadn’t had Jane’s first world concerns to give perspective to Esther’s third world ones.

SM: Maybe not.

BNR: It seems to me that the second plot (Jane’s) answers the crucial question she poses herself when she asks: “How could she be thinking so lightly of love, here in a place where people’s lips were cut off and girls were snatched out of their beds?” Maybe the second plot is Jane’s reply to that question — that it’s precisely in a place like this that it’s essential to think lightly of love.

SM: I would say the answer to Jane’s question is, because that is how the human mind works, drifting without discipline or measure much of the time.

BNR: Yet when the collision occurs, it doesn’t get any better that this. “They were beyond words now. Esther’s head leaned more heavily [on Jane’s shoulder] and Jane felt the close-cropped hair brushing against her chin.” It seems to fulfill, only momentarily but more beautifully, Jane’s need for physical closeness that she’s no longer getting from Harry. Something is released in Esther as she mumbles, even though we can’t hear what it is she’s mumbling “so weakly it sounded like the squeaks of a small animal.”

SM: They validate each other’s experience in some way. And it opens up something in both of them. In this moment their experiences overlap.

BNR: And that’s miraculous, isn’t it, as well as brave? The only thing more moving is the sense of longing throughout, perhaps even more strongly here than in your previous books. Both Esther and Jane experience it, though it’s given to Jane to articulate most poignantly in passages like this: “Her hand was flat on his chest feeling the sweat on his skin and she still had the longing to be closer. Would it ever stop? Did one ever get to a place where longing vanished?”

And so my final question to you is: Are any of your protagonists getting closer to such a place? Are you yourself?

SM: Longing, for everyone, is always there, isn’t it? More intense at some times than others. You get closer to less longing, an odd metaphoric phrasing I realize, then you are further and longing more than ever again…

BNR: Thank you. I just hope critics appreciate the risks you’ve taken here.

SM: We’ll see.

BNR: Meantime, take care of that index finger.

SM: I will.