How My Book Was Born: Close Your Eyes, Hold Hands Author Chris Bohjalian on Saying Goodbye

In four installments, author Chris Bohjalian is sharing the journey he took, from inspiration to publication, for his 2014 novel Close Your Eyes, Hold Hands, about a teen-girl runaway and aspiring poet surviving on the margins of Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom. Previously he’s spoken about his inspiration, his choice of a female narrator, and his process. In the final installment, he discusses the process of letting go.

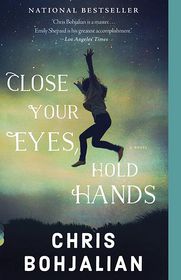

Close Your Eyes, Hold Hands

Close Your Eyes, Hold Hands

Paperback $15.95

When I finish writing a novel, I’m left with either deep postpartum sorrow or relief that a long, slow, unpleasant trudge through a swamp is behind me.

This is, of course, an oversimplification. There are degrees in between and there certainly have been books that left me feeling both. Some books are easier to write than others, and some books are simply better than others.

The reality is that I no longer presume every novel I write will be better than the one that preceded it. Years ago, I did. I hoped—I expected—that each new book would show growth. No more. I’ve written 17 novels, and at this stage in my career I liken what I do to being a Major League Baseball starting pitcher. I take the mound 30 to 35 times in a season, and if I am very good, I will win 20 times. But that means I’ll still lose a half-dozen times (at the very least), and throw a few absolute stinkers.

In any case, when I believe a novel has succeeded, I’m likely to experience mostly sadness when I review the final pages for the last time before they become a book. It’s not unlike the feeling we all have whenever we turn the last page of a novel that’s moved us—but it’s worse. Much worse. Why? Because I haven’t spent a weekend, a week, or even a month with those characters; I’ve been with them for a year. Or two. And now they are gone. I’ve greeted them every morning in my library about 6 a.m., and spent the next six hours with them, day after day after day. I have discussed them for hours (and hours) with my wife; I have debated (and psychoanalyzed) them with my editor and my literary agent.

When I wrapped up Close Your Eyes, Hold Hands, I felt mostly heartache. Certainly there was satisfaction, too. But I knew I was going to miss desperately my 17-year-old narrator Emily Shepard—and, as a father, I was going to continue to worry about her.

Make no mistake: it’s hard to say goodbye and move on. My books are not my children and I know my characters aren’t real; there is no crazy channeling going on, trust me. But when a novel touches us, it’s because there’s a human connection. And we all need that association. Think of what we say to each other.

“Tell me your story.”

“Tell me a story.”

I changed only one word in those short sentences, but the meaning is vastly differently.

In the first case? A request from a journalist, perhaps. A public defender. A social worker.

Imagine a novelist asking the question: Tell me your story. It’s research.

In the second? It’s a plea from one of our children: Tell me a story. Or maybe it’s an appeal from a lover who needs a respite from…life. From real life.

What the two constructions share is this: our infinite longing as human beings to hear stories, and our infinite capacity as people to create them. It’s not merely how we make sense of the world; it’s how we make sense of one another.

And this is, I imagine, why I do what I do. I love hearing stories and I love telling them—even though, alas, all stories end, and eventually we must all say good-bye.

Close Your Eyes, Hold Hands is available now.

When I finish writing a novel, I’m left with either deep postpartum sorrow or relief that a long, slow, unpleasant trudge through a swamp is behind me.

This is, of course, an oversimplification. There are degrees in between and there certainly have been books that left me feeling both. Some books are easier to write than others, and some books are simply better than others.

The reality is that I no longer presume every novel I write will be better than the one that preceded it. Years ago, I did. I hoped—I expected—that each new book would show growth. No more. I’ve written 17 novels, and at this stage in my career I liken what I do to being a Major League Baseball starting pitcher. I take the mound 30 to 35 times in a season, and if I am very good, I will win 20 times. But that means I’ll still lose a half-dozen times (at the very least), and throw a few absolute stinkers.

In any case, when I believe a novel has succeeded, I’m likely to experience mostly sadness when I review the final pages for the last time before they become a book. It’s not unlike the feeling we all have whenever we turn the last page of a novel that’s moved us—but it’s worse. Much worse. Why? Because I haven’t spent a weekend, a week, or even a month with those characters; I’ve been with them for a year. Or two. And now they are gone. I’ve greeted them every morning in my library about 6 a.m., and spent the next six hours with them, day after day after day. I have discussed them for hours (and hours) with my wife; I have debated (and psychoanalyzed) them with my editor and my literary agent.

When I wrapped up Close Your Eyes, Hold Hands, I felt mostly heartache. Certainly there was satisfaction, too. But I knew I was going to miss desperately my 17-year-old narrator Emily Shepard—and, as a father, I was going to continue to worry about her.

Make no mistake: it’s hard to say goodbye and move on. My books are not my children and I know my characters aren’t real; there is no crazy channeling going on, trust me. But when a novel touches us, it’s because there’s a human connection. And we all need that association. Think of what we say to each other.

“Tell me your story.”

“Tell me a story.”

I changed only one word in those short sentences, but the meaning is vastly differently.

In the first case? A request from a journalist, perhaps. A public defender. A social worker.

Imagine a novelist asking the question: Tell me your story. It’s research.

In the second? It’s a plea from one of our children: Tell me a story. Or maybe it’s an appeal from a lover who needs a respite from…life. From real life.

What the two constructions share is this: our infinite longing as human beings to hear stories, and our infinite capacity as people to create them. It’s not merely how we make sense of the world; it’s how we make sense of one another.

And this is, I imagine, why I do what I do. I love hearing stories and I love telling them—even though, alas, all stories end, and eventually we must all say good-bye.

Close Your Eyes, Hold Hands is available now.