Ichi-F Is a Powerful Manga Memoir of the Fukushima Disaster

For most of us, living outside Japan, the earthquake and tsunami of March 11, 2011, were viewed from a distance and through a screen—literally. Much of what we saw was aerial footage filmed from a birds-eye view; reporting from the ground was by necessity wide and shallow, showing us dramatic footage of the destruction but skipping quickly from place to place.

For most of us, living outside Japan, the earthquake and tsunami of March 11, 2011, were viewed from a distance and through a screen—literally. Much of what we saw was aerial footage filmed from a birds-eye view; reporting from the ground was by necessity wide and shallow, showing us dramatic footage of the destruction but skipping quickly from place to place.

Ichi-F: A Worker’s Graphic Memoir of the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant does the opposite: it goes narrow and deep, pulling us into the day-to-day life of an ordinary guy doing an extraordinary job—working on the cleanup and repair of the Fukushima Daiuchi nuclear power plant that suffered three meltdowns, an explosion, and a major release of radioactive material after losing power in the wake of the tsunami.

Kazuto Tatsuta (a pseudonym) decided to go to work at Ichi-F for two reasons: To see what life was really like inside the contaminated area, and to rake in the big yen that came with a high-risk job.

Debug Notice: No product response from API

It didn’t quite work out as planned. He started out working in the rest area, keeping the coolers stocked with bottled water and sports drinks, making sure there was plenty of protective gear on hand as workers came and went from the contaminated zones, and refueling the generators that ran the refrigerator and the air conditioners (generators, even though, he reflected on a particularly sweltering day, they were inside a power plant).

As for the big bucks, they weren’t exactly forthcoming. The way the work is organized at Ichi-F is confusing, with six or seven layers of subcontractors between the workers and the main contractor. Most of the lower-level guys are sketchy. So when Tatsuta first came on site, he stayed in an overcrowded dorm, paying for lodging and meals, but not making any money at all, because there was no work for him yet. Once the work did start, room and board took a big bite. Eventually, he and two co-workers bought a car and rented a house, and he got some real construction work inside the plant. Things got better. Still, the radiation restrictions were such that the workers spent more time suiting up and resting than actually working, and the number of days they could work were limited. In short, the job didn’t make him rich.

Tatsuta keenly depicts the human side of Fukushima, including the personalities of his co-workers. One was a former member of the security forces whose lifetime radiation exposure was too high for him to ever work in the hotter areas again, while others had lost their homes in the tsunami. Then there was the peculiar ambivalence of outsiders: the workplace was festooned with thank-you banners from schools all over Japan, but the locals wouldn’t rent them a car for fear it would be contaminated (even though they would not be allowed to drive it anywhere near the radioactive areas). The manga-ka has an eye for the telling detail, such as the break room where the floors and walls were yellow from accumulated cigarette smoke, or the way workers exchanged information when they turned over the work to a new shift.

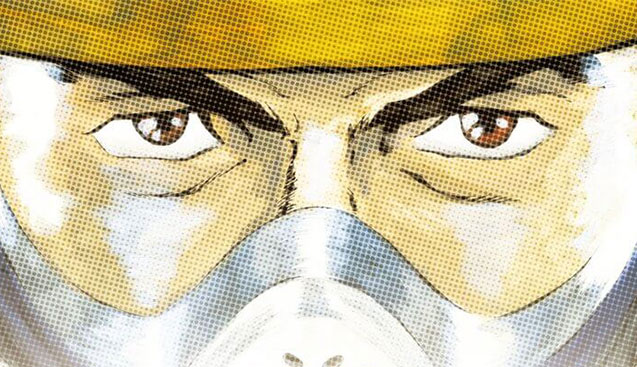

For something that seems so otherworldly, Ichi-F has a lot of earthiness to it. Tatsuta starts off by taking us through the different layers the workers must take off and put on as they move from area to area within the grounds of the plant. He even shows us the four different types of face masks, with commentary on each, and later reveals the thing that bothered him the most was not the fear of radiation, but not being able to scratch his itchy nose while wearing a taped-on filter mask.

There are details of the toilets (pixelated at times to spare the reader’s sensibilities), the constant checks for radiation exposure, the little luxuries in the rest areas. He even draws maps and schematics of the power plant and the individual buildings. Every now and then, he busts out into landscape mode to show a larger view of the devastation—the framework of the Unit 3 reactor silhouetted against the sky is a recurring motif, the houses in the nearby villages choking under wild vegetation.

As he tells his story, Tatsuta occasionally pauses to debunk some urban legend or to explain how the safety procedures have been tweaked to stop unscrupulous subcontractors from cutting corners. He also describes how difficult it was to change jobs—all the negotiations were on the down low, as workers aren’t supposed to move from one subcontractor to another.

The first chapter of the manga was originally drawn as a one-shot comic, and the second chapter repeats it a bit. At first the material may seem a bit dry, but as he goes on, Tatsuta loosens up, and we get to see him playing old folk songs on his guitar and checking out the local food and sights. (He fills a whole page with a discussion of the coffee drink he favored while on the job.) He also talks about how he came to draw this manga, and the tension it occasionally caused him, especially when he was being covered by the media (some of whom brought their own agendas to the interviews).

Tatsuta is a workmanlike artist with an eye for detail, and Ichi-F doesn’t have the extreme stylization that one finds in more genre-oriented titles. His foreshortening gets a bit wobbly at times, but the characters have expressive faces, and he has a talent for pulling you into a scene. The book has been flipped so it reads left to right, and that, combined with Tatsuta’s straightforward style, makes this manga very accessible even to non-manga readers.

Kodansha has also done a nice job with the presentation. The manga is collected in a three-in-one omnibus containing the entire story, with translator’s notes at the end of each of the original volumes. Extras include an introduction by journalist Karyn Nishimura Poupée and an exclusive interview with the author.

If you’re someone who likes to get the inside story, with all the messy procedural details, this you will find this book deeply satisfying from page one. Others may find it slow to start, but once Tatsuta gets warmed up, Ichi-F becomes a very rich story, populated by interesting characters and loads of juicy details, and a vital continuing commentary on the progress that was made over the three years he spent inside—and outside—of the Fukushima power plant.

Ichi-F: A Worker’s Graphic Memoir of the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant is available now.

It didn’t quite work out as planned. He started out working in the rest area, keeping the coolers stocked with bottled water and sports drinks, making sure there was plenty of protective gear on hand as workers came and went from the contaminated zones, and refueling the generators that ran the refrigerator and the air conditioners (generators, even though, he reflected on a particularly sweltering day, they were inside a power plant).

As for the big bucks, they weren’t exactly forthcoming. The way the work is organized at Ichi-F is confusing, with six or seven layers of subcontractors between the workers and the main contractor. Most of the lower-level guys are sketchy. So when Tatsuta first came on site, he stayed in an overcrowded dorm, paying for lodging and meals, but not making any money at all, because there was no work for him yet. Once the work did start, room and board took a big bite. Eventually, he and two co-workers bought a car and rented a house, and he got some real construction work inside the plant. Things got better. Still, the radiation restrictions were such that the workers spent more time suiting up and resting than actually working, and the number of days they could work were limited. In short, the job didn’t make him rich.

Tatsuta keenly depicts the human side of Fukushima, including the personalities of his co-workers. One was a former member of the security forces whose lifetime radiation exposure was too high for him to ever work in the hotter areas again, while others had lost their homes in the tsunami. Then there was the peculiar ambivalence of outsiders: the workplace was festooned with thank-you banners from schools all over Japan, but the locals wouldn’t rent them a car for fear it would be contaminated (even though they would not be allowed to drive it anywhere near the radioactive areas). The manga-ka has an eye for the telling detail, such as the break room where the floors and walls were yellow from accumulated cigarette smoke, or the way workers exchanged information when they turned over the work to a new shift.

For something that seems so otherworldly, Ichi-F has a lot of earthiness to it. Tatsuta starts off by taking us through the different layers the workers must take off and put on as they move from area to area within the grounds of the plant. He even shows us the four different types of face masks, with commentary on each, and later reveals the thing that bothered him the most was not the fear of radiation, but not being able to scratch his itchy nose while wearing a taped-on filter mask.

There are details of the toilets (pixelated at times to spare the reader’s sensibilities), the constant checks for radiation exposure, the little luxuries in the rest areas. He even draws maps and schematics of the power plant and the individual buildings. Every now and then, he busts out into landscape mode to show a larger view of the devastation—the framework of the Unit 3 reactor silhouetted against the sky is a recurring motif, the houses in the nearby villages choking under wild vegetation.

As he tells his story, Tatsuta occasionally pauses to debunk some urban legend or to explain how the safety procedures have been tweaked to stop unscrupulous subcontractors from cutting corners. He also describes how difficult it was to change jobs—all the negotiations were on the down low, as workers aren’t supposed to move from one subcontractor to another.

The first chapter of the manga was originally drawn as a one-shot comic, and the second chapter repeats it a bit. At first the material may seem a bit dry, but as he goes on, Tatsuta loosens up, and we get to see him playing old folk songs on his guitar and checking out the local food and sights. (He fills a whole page with a discussion of the coffee drink he favored while on the job.) He also talks about how he came to draw this manga, and the tension it occasionally caused him, especially when he was being covered by the media (some of whom brought their own agendas to the interviews).

Tatsuta is a workmanlike artist with an eye for detail, and Ichi-F doesn’t have the extreme stylization that one finds in more genre-oriented titles. His foreshortening gets a bit wobbly at times, but the characters have expressive faces, and he has a talent for pulling you into a scene. The book has been flipped so it reads left to right, and that, combined with Tatsuta’s straightforward style, makes this manga very accessible even to non-manga readers.

Kodansha has also done a nice job with the presentation. The manga is collected in a three-in-one omnibus containing the entire story, with translator’s notes at the end of each of the original volumes. Extras include an introduction by journalist Karyn Nishimura Poupée and an exclusive interview with the author.

If you’re someone who likes to get the inside story, with all the messy procedural details, this you will find this book deeply satisfying from page one. Others may find it slow to start, but once Tatsuta gets warmed up, Ichi-F becomes a very rich story, populated by interesting characters and loads of juicy details, and a vital continuing commentary on the progress that was made over the three years he spent inside—and outside—of the Fukushima power plant.

Ichi-F: A Worker’s Graphic Memoir of the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant is available now.