Jeff VanderMeer: Wonderbook

Jeff VanderMeer‘s Wonderbook carries the modest subtitle “The Illustrated Guide to Creating Imaginative Fiction,” — an understated indication that, perhaps, a few visual treats will enliven a new entry in the ever-crowded field of how-to books for writers. In fact, what the author of the Ambergris Cycle and longtime writing teacher has offered would-be creators of fantasy and speculative fiction is an overstuffed candy store for the eye and brain, with nearly every one of Wonderbook’s three-hundred-plus pages bursting into idiosyncratic and colorful life.

The result is at once a writer’s inspiration, a reader’s companion and a browser’s delight. A minutely detailed graphic at Wonderbook‘s opening maps the history of science fiction against a Ward Shelley illustration suggesting blood coursing through the body; a chapter on “The Ecosystem of Story” is arranged around an eye-popping painting by Robert Connett, while an interview with George R.R. Martin about the craft behind A Song of Ice and Fire uses a photo of Hadrian’s Wall to embody the archaeological roots of a fantasy master’s creation – much as a fisheye view of Samuel Delaney in his study offers an inspiring peek into a writer’s physical environment.

The spine of the book is serious business: as a three-time World Fantasy Award winner (both as editor and writer) and Nebula nominee for 2009’s surreal noir Finch, VanderMeer draws on the full range of his experience to deliver a wide-ranging discussion of the possibilities and pitfalls for storytellers, and consults with a host of literary luminaries to get their takes on nearly every aspect of the creative process, particularly those (worldbuilding, for example) of writers working outside of realism’s frame.

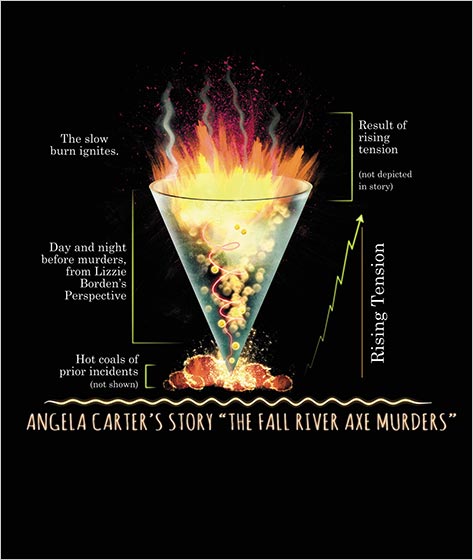

But his collaboration with the artist Jeremy Zerfoss (whose work also appears on the cover) generates visual treatments throughout that transform a primer on the writer’s craft into a tour of a Willy Wonka-like fiction factory: Chinese dragons take you through how to write a character’s day, narrative “beats” are examined under the microscope, a short story by Nabokov is analyzed via astronomy. Nor all the “illustrations” only visual: short essays from an awe-inspiring array of contributors — Ursula K. Le Guin, Kim Stanley Robinson, Charles Yu, Karen Joy Fowler, Lev Grossman, and Neil Gaiman, to name a few — let would-be novelists in on the struggles and experiences of those who have already found their voices.

We reached Jeff VanderMeer at his home in Tallahassee, Florida, and persuaded him to take a break from working on his forthcoming Southern Reach Trilogy (which opens with Annhiliation, coming in early 2014) to talk with the BNR via email about Wonderbook. — Bill Tipper

The Barnes & Noble Review: How would you describe Wonderbook?

Jeff VanderMeer: An attempt to fuse the practical and the impractical — to create something that is intrinsically fun just for its own sake, but that also provides what any beginning or intermediate writer might need to work on the craft and art of their writing. I wanted it to have stories spiraling through it as well in the text, so the text would evoke images as well — you’ll note that a talking penguin is a recurring character in the text, among other characters. That also speaks to the idea of so many books being so serious — you can be deeply non-serious and still focused, disciplined, and on task. I also wanted the book to feature its own insurgency, so the disruption dragons, and their text, begin to call into question aspects of my main text. This is the normal process with a writing book: writer encounters it and agrees with some things and disagrees with others. In that confluence — knowing what resonates for you and what doesn’t — you find out who you are as a writer. I also hope that Wonderbook is a celebration of creativity that interests non-writers. Some of the exercises in particular are meant to energize and inspire someone who might like to write a story but not pursue a career as a writer. And I think this is true to what creativity is all about, because we all tell stories to each other.

Jeff VanderMeer: An attempt to fuse the practical and the impractical — to create something that is intrinsically fun just for its own sake, but that also provides what any beginning or intermediate writer might need to work on the craft and art of their writing. I wanted it to have stories spiraling through it as well in the text, so the text would evoke images as well — you’ll note that a talking penguin is a recurring character in the text, among other characters. That also speaks to the idea of so many books being so serious — you can be deeply non-serious and still focused, disciplined, and on task. I also wanted the book to feature its own insurgency, so the disruption dragons, and their text, begin to call into question aspects of my main text. This is the normal process with a writing book: writer encounters it and agrees with some things and disagrees with others. In that confluence — knowing what resonates for you and what doesn’t — you find out who you are as a writer. I also hope that Wonderbook is a celebration of creativity that interests non-writers. Some of the exercises in particular are meant to energize and inspire someone who might like to write a story but not pursue a career as a writer. And I think this is true to what creativity is all about, because we all tell stories to each other.

BNR: Wonderbook is not your first book of resources for writers – that would be Booklife. But it’s the first time you’ve drawn so much on a visual language – evocative illustrations, book covers, photography, and most arrestingly the vibrant charts/graphs/maps by Jeremy Zerfoss, which take issues like story structure, plot and character development, and many of the architectural and conceptual aspects of the writer’s work, and render them visually. What first prompted you to use this method for Wonderbook? Did you have models in mind?

JV: I have to give love and props to Abrams Image. They wanted another book after The Steampunk Bible and I jumped at the chance to do what’s basically a coffee table creative writing book. It was truly energizing because my mom is an artist and my own fiction is deeply visual, so although I’d wanted to do a book on the craft and art of writing it wasn’t until this opportunity came along that everything just clicked into place. It just seemed natural to me. I wish I could say I had models in mind. The best visual book I can think of is Lynda Barry’s What It Is, but although I refer to it all the time it’s not a creative writing book per se. When I did some research, I actually found very little of a visual nature that was creative-writing related, except for some basic diagrams. So one reason the book took two years to produce was that we were working our way toward what did and didn’t work visually. Nothing to mimic. Jeremy was amazing because he was willing to try anything. I’d say, “We’re going to see what a Story Lizard looks like” and he’d jump on it. I’d say, “We’re going to portray the lifecycle of a story like the lifecycle of a tadpole to a frog-critter” and he’d say “Yes!” So a lot of what we accomplished was possible because I’d take a leap and Jeremy would follow me — all in.

(Below: Illustration from Wonderbook by Jeremy Zerfoss, courtesy Abrams Image)

BNR: How did Jeremy Zerfoss’s ideas play into yours? Did you collaborate on the form those graphic “processes” would take?

JV: Usually, I’d do a rough sketch and Jeremy would either provide a proof-of-concept sketch or a rough full version. We had a style sheet I’d come up with that basically rendered everything down to types: two-dimensional diagram, three-dimensional art, etc. But along the way, Jeremy created the little alien guides who keep up a running dialogue throughout the book, and some of their dialogue Jeremy just came up with himself. And sometimes Jeremy would just send me some weird image and I’d say “That’s perfect for so-and-so,” and then it’d be me kind of adjusting his work to fit the book. It was fairly intense working on something this unique…so the volume of communication back and forth was pretty intense as we figured things out. I think I have ten thousand emails from Jeremy while we collaborated. We also posted a lot of Jeremy-and-Jeff images on Facebook, to de-stress and poke fun at the whole process. Jeremy was truly amazing.

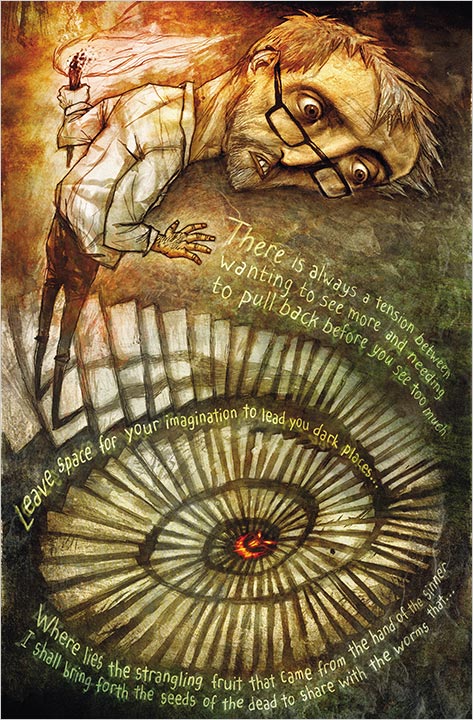

BNR: So much of your fiction draws its energy from uncanny interpenetrations – in particular things that are alive in ways that are unexpected or disturbing. There’s a sense reading the book that those category-confusion moments are a key part of your creative method; in essence, the embracing of that interpenetration of the real and the fantastic is the “Wonder” at the heart of the “Wonderbook.” Do you think that’s accurate?

JV: That seems accurate to an extent. It kind of gets at why I’m avoiding the word “whimsical,” which has some negative light-as-air connotations. But what is the word? My worldview sees the fantastical in the mundane and adores the fantastical in our world. I’m also a big believer in the Surrealists’ idea of “unexpected beauty in the service of liberty.” Angela Carter, Leonora Carrington, even nonsurrealists like Kafka and Nabokov — writers like these, who create paths between the firmly grounded and flights of fantasy, are my personal North Star. This manifests in a strong sense of play, but also in an underlying appreciation for and expression of darker things. The trick is express that while, in the context of something like Wonderbook, creating something that speaks broadly to most writers. I didn’t want to create a private playground with its own special passwords but something expansive and inclusive. This is one reason why so many other voices, from all over the world, are in the book.

BNR: There are some wonderful contributions in the form of short essays from writers like Ursula K. Le Guin, Neil Gaiman, Karen Joy Fowler, and many others. How did you work with them? Did you ask them to attack specific subjects? Or just say “Please talk about your writing?”

JV: Thank you for appreciating the essays. I chose these pieces very carefully. A couple are reprints, but in the case of the originals, I wanted to accomplish a few things: to get the necessary expertise in areas I don’t feel as accomplished in, to, in some cases, have someone readers assume is expert in the topic address it, and in other cases to have a writer address a topic I believed they were expert in but they’re not widely known for. So, for example, I could have had David Anthony Durham talk about his fantasy novels, but I thought it was more interesting to have him discuss his historical novels. Joe Abercrombie has a novel, Heroes, set during three days of battle in the same location, so having him talk about the decisions he made in the context of a map of the battlefield seemed useful. And that’s not even including the interviews I conducted for the book and then quoted from in the main text.

BNR: I found the interview with George R.R. Martin revealing — and of course anyone who is a fan of the books is likely to be interested – but what’s remarkable is that he really opens up about his approach to writing as a craft, but also about the small touches, favorite scenes or images. Readers of such a long fantasy epic might lose sight of how much those little moments mean.

JV: I had noticed that many of his internet interviews on craft were relatively short or switched half-way through to talk about the TV series. So I thought it would be interesting to do a long interview with him about craft, one that maybe moved beyond some of the basic things he’d covered before. We talked on the phone for about an hour, and the results were great. I wanted to ask him about specifics, because I believe the best creative writing lessons live in the specifics — in being asked about what this meant, or how this worked. I also wanted to ask a lot about pacing but also about something that may seem counterintuitive: the strangeness of his fiction. He’s written these mega-bestsellers, but there are so many really weird and non-commercial moments in them.

BNR: Which are the aspects of craft discussed in this book you still struggle with the most as a writer?

JV: I actually decided to let those moments show through in the book in some places. I’ve always wrestled with the difference between plot and structure, and after re-reading a lot of other writing books I realized I wasn’t alone. So the first part of the chapter on Narrative Design basically says, “Look, every writer has at least a slightly different idea of what plot is and what structure is, so let’s talk about that before we move onto more concrete aspects of narrative design.” It more or less boiled down to the fact that I arrive at plot through character and structure: there is a character creating a structure, and the beats and progressions therein create plot. And for that reason, talking in terms of plot is not personally useful to me. But since it is for others, there is also concrete discussion of plot in the book. One of the most important things as a writing instructor is to provide a lot of different entry points to subjects. To not impose your own personal experience as the One True Way. Hopefully, Wonderbook reflects that.

(Below: illustration from Wonderbook: “There Lies the Strangling Fruit” by Ivica Stevanovic, courtesy Abrams Image.)

BNR: One of the things that Wonderbook implicitly addresses is the explosion of venues/possibilities for writers of fiction, particularly for writers of speculative fiction and related modes — the whole confluence of science fiction, fantasy, horror, the gothic, the weird tale, which is so appealingly mapped right at the start of the book. But with this explosion of venues comes a real change in the traditional relationships of writer to editor, and writer to market — perhaps better to say, today, writer to community. Have the conditions of creativity changed as radically for writers in the last decade as the broader landscape of reading, in which fan fiction, blogged creations, and live-action role playing (LARP) projects exist cheek-by-jowl with self-published ebooks and traditionally published books?

JV: It’s definitely a golden age of storytelling, across so many different platforms and media, even as everyone’s uncertain about the future. As always, there’s the usual amount of crap, but in every nook and corner you can find something interesting and fresh. Across all of this universe of creative lying, whether you believe in the art of it or the entertainment of it, or both, a certain foundation in the basics allows you to kind of jump out into the unknown. I usually give the example of the experimental writer. The experimental writers I like best first learned the traditional basics — and then rejected the traditional. But they learned it first. Beyond the basics, the fascinating and energizing storytelling comes from the cross-pollinations, the re-combinations and mutations. One way Wonderbook does that is by putting different kinds of writers in conversation with each other on the page, so to speak — you’ve got Le Carré next to Angela Carter next to Amos Tutuola next to Nnedi Okorafor and Lev Grossman, etcetera. Not to mention sections on fiction from the perspective of LARP and game creation. Some very complex creative writing concepts can be more easily conveyed through these adjacent forms of storytelling.

BNR: Can you talk a little about the novel you have coming out in early 2014? It’s the first of a new trilogy, correct?

JV: Annihilation is the first of my Southern Reach trilogy, which also includes Authority and Acceptance (also out in 2014), out from FSG. It’s the story of a biologist who is part of an expedition into a strange wilderness called Area X, surrounded by an invisible border, which has defeated eleven previous expeditions. The biologist is bringing her own secrets with her, and what the expedition’s been told may or may not be accurate about Area X. There’s a somewhat mysterious lighthouse and something odd moaning in the reeds along the coast. The books describe the search for the cause of Area X, a search conducted by a secret government agency called the Southern Reach — book two is actually set mostly in the Southern Reach, back across the border. It’s a very personal story for me, and really the series is about how people react when they come up against the truly inexplicable and about our relationship to nature. Paramount has optioned the series, too.

BNR: You conclude with exercises for the reader/writer — my favorite involves “collecting textures” — do you have any that are personal favorites? Any you make sure all of your own students take on?

JV: Well, collecting textures is a favorite, too — just because we once sent our students roving to find textures and caught one of them for quite some time agonizing over whether or not to lick a rock! I find the “Leonardo” exercise, which gives a writer a set plot, structure, and characters, very useful. One thing about beginning writers is that they don’t really always know their own strengths and weaknesses — you might think you’re bad at characterization, but that might really be because of some issue you’re having with another element, which is making it hard for you to express character in a convincing way. So when you’re given elements you otherwise have to come up with on your own — they’re handed to you — you can relax into the story and you sometimes find out new things about your writing.

–October 9, 2013