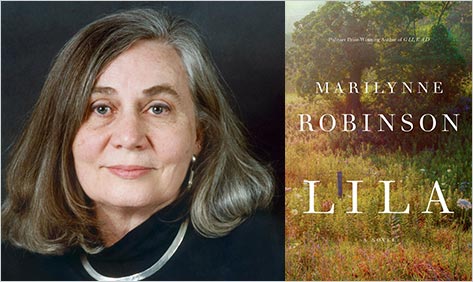

Marilynne Robinson: A Good Inheritance

A new Marilynne Robinson novel is a rare treat. Lila, just published by FSG and already nominated for this year’s National Book Award for Fiction, continues the story she began in the Pulitzer Prize–winning novel Gilead and returned to in Home. Ever since her first novel, Housekeeping, came out in 1980, Robinson’s words have resonated with readers. There’s nothing flashy in her prose and something of another generation about her style. There’s a gentle urgency to it that unfolds gracefully. Her books are even more revelatory the second time around. It’s easy to miss the subtleties when you’re initially so engaged in the narrative.

A new Marilynne Robinson novel is a rare treat. Lila, just published by FSG and already nominated for this year’s National Book Award for Fiction, continues the story she began in the Pulitzer Prize–winning novel Gilead and returned to in Home. Ever since her first novel, Housekeeping, came out in 1980, Robinson’s words have resonated with readers. There’s nothing flashy in her prose and something of another generation about her style. There’s a gentle urgency to it that unfolds gracefully. Her books are even more revelatory the second time around. It’s easy to miss the subtleties when you’re initially so engaged in the narrative.

In Lila, Robinson tells the story of the minister’s wife, who we’re first introduced to in Gilead. Lila comes from a tough upbringing. She is stolen away from a bad family situation by a woman named Doll and spends much of her childhood on the road with Doll and fellow drifters. She works in a whorehouse before finding her way to the town of Gilead. She first meets John Ames at his church, and a relationship slowly blooms between them, despite her reluctance to let anyone get close to her. “She knew he was thinking and praying about how to make her feel at home,” Robinson writes. “She had never been at home in all the years of her life.” Our homes and where we come from have always been a central theme in Robinson’s work: she excels at writing about lonely people who are trying to find spaces of their own. Lila is a testament to how love, both romantic and familial, can sustain us.

Last month, I asked Robinson some questions via email about her marvelous novel. – Michele Filgate

The Barnes & Noble Review: In Gilead, you focused on the Reverend John Ames. In Home, you tell the story of Ames’s friend Reverend Robert Boughton and his family. In Lila, we return to the same town and learn about the life of Reverend Ames’s wife. How difficult was it to revisit characters in each subsequent book? Did you already have their back-stories mapped out?

Marilynne Robinson: I have found that the characters in my novels stay with me after a book has ended. I know them in some sense. I never map anything out. I just think until I am secure in the voice of one of them, and then let the character unfold.

BNR: Loneliness is something that bonds the Reverend and Lila — and it’s no surprise. The Reverend lost his first wife and newborn child, and Lila came from a tough background. At one point, you say: “He looked as if he’d had his share of loneliness, and that was all right. It was one thing she understood about him.” Does this mutual comprehension make them outsiders — or just regular humans, trying to make sense of their lives?

MR: They are regular humans who have been sensitized by experience to the fact that loneliness is a major part of any life. I think that there is a tendency in our society now to treat social ties as a measure of personal health or worth. So people don’t acknowledge loneliness in themselves, and don’t appreciate its benefits, the reflection and attentiveness that come with it, the deepened acquaintance with oneself. Granting, of course, that there can be too much of a good thing.

BNR: Lila isn’t educated. She’s smart and excelled in her one year of schooling, but she lived a life on the go with drifters and she looks to the Reverend for knowledge. Yet she’s philosophical and curious about the meaning of life — and that leads her to exploring religion. The woman who stole her away and raised her (Doll) and the group of people she grew up with were not religious, and they didn’t turn out so well, despite those of them who had good intentions. How do you think about the relationship between formal education and faith.

MR: Most institutions of higher learning in the West were founded by and for religious denominations. The supposed alienation of education and faith is a recent phenomenon. At the same time, neither education nor the lack of it predisposes one to faith. The people Lila grew up with are essentially outside the culture in which the language and sacraments of religion are taught and learned. But they are as good as most people, even though they have so much difficulty to deal with. Things turn out badly for them because they are poor during the Depression. This has nothing to do with their not being religious.

BNR: Trust is a big issue for Lila. She doesn’t trust anyone: not even Doll, who rescues her as a child. How can people navigate through the complicated world that we live in when it’s hard to believe anyone?

BNR: Trust is a big issue for Lila. She doesn’t trust anyone: not even Doll, who rescues her as a child. How can people navigate through the complicated world that we live in when it’s hard to believe anyone?

MR: People have been through times infinitely more difficult than these. I think we need a better sense of history. A great deal that is of value has been maintained and created through oppression, plagues, famines, and persecutions. If we focused on using the opportunities we have, which are very great by any standard — health, longevity, comfort and privacy, endless resources of culture and information — we would not just navigate this world, we would leave a good inheritance to succeeding generations.

BNR: At one point when talking about Lila, you write: “There was more shame in life than she could bear.” She stays in a shack when she first moves to Gilead, just trying to survive. “Life is hard in the spring, and still it all felt like something she had almost died for the want of.” Despite all this hardship, she comes through as a fighter. Does that set her apart from your other characters?

MR: It is hardship that makes clear who the “fighters” are. None of the other characters have exactly her difficulties to deal with, but that doesn’t mean they don’t have their own, or that they would not deal with hardships that came to them. Their immediate ancestors were frontier Abolitionists. No one was ever tougher than that. More generally, people who lived in a period when maternal, infant and childhood mortality were still high would have been tougher than most of us can imagine.

BNR: Right after she marries the Reverend, she notices him praying in their house. “And then she thought, ‘Praying looks just like grief. Like shame. Like regret.’ ” Is sadness or grief necessarily linked to revelation?

MR: No. But they inevitably deepen understanding.

BNR: Can you talk a little bit about the origins of the characters in Gilead? Did you know when you started writing that novel that it would lead to other books?

MR: Characters more or less present themselves to me. I don’t know their origins. I think if I did, if I seemed to myself to fabricate them, I could not induce suspension of disbelief in myself in the way writing fiction requires. The mind has a complex life that can seem quite autonomous—dreams, obsessions, unwilled memory are all instances of this. It is true that I have been attentive to history and theology in ways that determine the world of these novels. I did not intend to write the other books when I wrote Gilead.

MR: Characters more or less present themselves to me. I don’t know their origins. I think if I did, if I seemed to myself to fabricate them, I could not induce suspension of disbelief in myself in the way writing fiction requires. The mind has a complex life that can seem quite autonomous—dreams, obsessions, unwilled memory are all instances of this. It is true that I have been attentive to history and theology in ways that determine the world of these novels. I did not intend to write the other books when I wrote Gilead.

BNR: Are there particular books or writers that informed your thinking about Lila?

MR: I suppose I am influenced by any number of books, and books in general. I saw a quote from Robert Schumann to this effect — Composing music is remembering a song no one has ever heard before. I like a book to be full of the memory of what it is, a voice in an endless conversation, and yet at the same time to be new.

BNR: You write both fiction and nonfiction. Do you enjoy writing one more than the other? What are the unique challenges of each genre?

MR: I like to work on one or the other, depending on what is on my mind. The challenges are too particular to each piece of work to characterize the genre.

BNR: How important is plot to you — do you think in sentences, characters, or timelines?

MR: Character, then sentence, though each is entirely dependent on the other. I find that timelines more or less take care of themselves.

BNR: What’s the number one piece of advice you give your graduate students at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop?

MR: Never, ever condescend to the reader. Assume you are writing for someone better and smarter than you are. This will protect you from conventionalism, faddishness, and cliché.