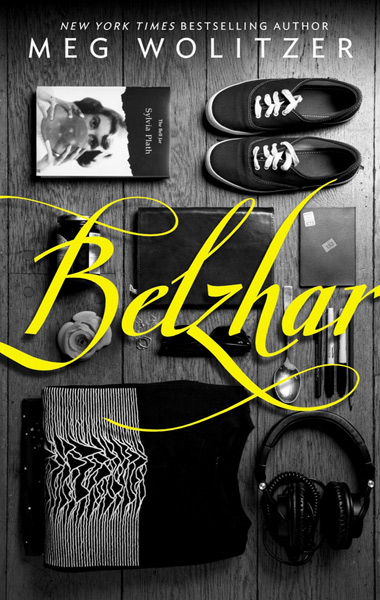

Meg Wolitzer’s YA Debut, Belzhar, Turns Grief Into A Special Realm

Who isn’t emotionally fragile at some point in their teen years? And who doesn’t long to be picked out of the crowd, recognized as someone special, either because of the heightened nature of their feelings or some other intangible quality only other special people can see? That’s why the Wooden Barn, a New England boarding school for “emotionally fragile, highly intelligent” students, and its selective class Special Topics in English (featuring lots of dark poetry and journaling), sounds like the setting of our adolescent dreams. But that’s not the only fantasy offered to the damaged students in Meg Wolitzer’s first YA novel, Belzhar.

Who isn’t emotionally fragile at some point in their teen years? And who doesn’t long to be picked out of the crowd, recognized as someone special, either because of the heightened nature of their feelings or some other intangible quality only other special people can see? That’s why the Wooden Barn, a New England boarding school for “emotionally fragile, highly intelligent” students, and its selective class Special Topics in English (featuring lots of dark poetry and journaling), sounds like the setting of our adolescent dreams. But that’s not the only fantasy offered to the damaged students in Meg Wolitzer’s first YA novel, Belzhar.

Jamaica “Jam” Gallahue’s parents send her away from their home in Crampton, New Jersey (yep, a town name doesn’t get more on-the-nose than that), because she can’t seem to get it together almost a full year after the death of her boyfriend, British exchange student Reeve Maxfield. “After I met him, the kinds of love I’d felt for those other people suddenly seemed basic and lame,” Jam tells us early on, comparing this new love to higher math. His sense of humor matches hers exactly, and they click instantly. Her brief relationship with Reeve also set her apart from her group of “low-key nice girls with long hair” and got her noticed by the in crowd.

Now, after months of locking herself in her room in a stasis of grief, Jam is again picked out of the crowd as one of the five students of the Special Topics class. Mrs. Quenell, a teacher so ancient she still goes by her last name, tells the students they’ll be studying Sylvia Plath all semester, as well as writing about their feelings twice a week in antique, red-leather journals. As she passes these out, she assures the students: “Everyone has something to say. But not everyone can bear to say it. Your job is to find a way.” And your job, reader, is to bear with that sentimentality for a moment and get to the good stuff: what happens when they do find that way.

When Jam finally manages to write one line in the notebook, she’s sucked into another reality, where she finds herself lying in the field behind her old school with Reeve. She’s allowed to spend time with him, reliving some of their best moments together, and when she returns to this world, she finds five pages filled in her own handwriting. The same thing happens to the other students, each suffering their own, slowly revealed tragedies. Everything they lost is restored, albeit for a few hours. They meet at night to share their experiences, which are far too real to be called dreams. “I feel like we’re a group of grade-schoolers trying to name their crime-solving or bottle-recycling club,” Jam tells the reader when she comes up with the name Belzhar (pronounced BEL-jhar, as in Plath’s Bell Jar). Yet the name and the rules they establish about when and how often to go there not only make their journeys feel more real, as Jam puts it, they also draw the group closer together. Now their specialness is tangible.

In The Interestings, Wolitzer’s characters also form a tight-knit group in the dark like this, but that adult novel throws grown-up life in their way, smashing the cocoon of their summer camp, Spirit-in-the-Woods, and destroying their notion of being something better than anyone else. Wolitzer is much gentler to Jam and her friends—the intellectual edge and introspection that gave The Interestings its sharpness is softened here in favor of a lesson. There is a twist, however, and even if you see it coming, you might agree that it’s weird enough to keep things, well, interesting.

“Please, look out for one another,” Mrs. Quenell urges her students. And, in fact, they learn that by supporting each other, they can slowly find the strength to step out of their magical worlds. They’ll be less special once they break out of those bell jars, but maybe that’s not such a bad thing.

Belzhar is out now.