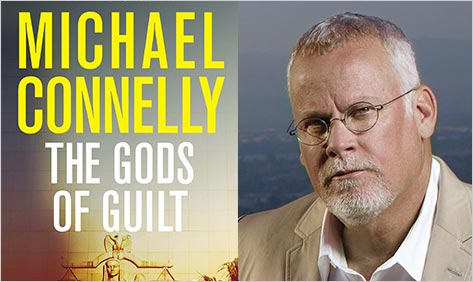

Michael Connelly: The Gods of Guilt

It can be a little startling, for those of us who follow series fiction, to watch the growing space a writer occupies on our bookshelves and realize the amount of time we’ve been keeping with each other over the years. The Gods of Guilt is Michael Connelly’s twenty-seventh novel since his 1993 debut, The Black Echo, which introduced his steadiest protagonist, Los Angeles police detective Harry Bosch. The Gods of Guilt is Mickey Haller’s show. “The Lincoln Lawyer,” as he’s known, is still conducting business from the back of his sedan, still walking the ethical edge to do right but his clients, and, in this installment, haunted by the way that duty has cost him the affection of his teenage daughter whose friends were killed by a client Mickey freed. The case he’s tackling in The Gods of Guilt centers on a former client, a woman he believed had left sex work behind, but who ends up dead and whose accused killer Mickey defends.

The reigning writer of LA noir, Connelly took time for an email correspondence with B&N Review to answer questions about what unites Mickey Haller and Harry Bosch, the place of crime fiction in today’s literary world, and how his own writing process has changed one the years. — Charles Taylor

The Barnes & Noble Review: Mickey Haller tells us that the title The Gods of Guilt is lawyer slang for the jury. And guilt takes many forms in the book, not just what those gods will decide but the burden Mickey carries with him. Can you talk a little about the virtues of guilt as both dramatic device and as something that allows you to explore your hero’s psyche?

Michael Connelly: I think it was Raymond Chandler who said there is a quality of redemption in anything that is art. I believe it and so I think that if you have a character in a book who is operating with a sense of guilt then he is a character seeking redemption. This can be very dramatic. In this book I think the heart of the story is Mickey struggling with the guilt of having damaged his relationship with his daughter. He wants her back. That’s his redemption and in his way, he sees a not guilty verdict in his case as a means to that redemption.

BNR: Mickey Haller gets to take shortcuts that Harry Bosch couldn’t. Is part of the pleasure of writing the character finding ways to indulge that defense lawyer’s craftiness?

MC: Yes, Harry has more rules and he is also the one with the noble mission. So when I write about Mickey I feel this freedom to really go down into the trenches of the justice system. I know that no matter what short cuts he takes or how off his moral compass seems to be, I can always bring him into the good graces of the reader by the end.

BNR: Do you see consonances between these two characters?

MC: I think on a very broad level they are moving on the same plane. They want to do the right thing. They have daughters of similar age and they want the world to be better for them. There are commonalities we all share and I would start there for them. I think they both dwell in a gray world and by that they know that the cops don’t always get it right, that the justice system is something that is malleable.

BNR: Los Angeles has been the background for some of the giants of crime writing, Chandler and Ross Macdonald among them. How do you think the city specifically feeds your work, and why does it continue to be such fertile ground for the genre?

MC: It’s a destination location, one of those cities that people go to because wherever they are from does not work for them. That consequently builds this iconic idea of the place where dreams are fulfilled. But that only happens for a small percentage of the weary travelers who get here. There are more have-nots than haves. You have a lot of isolation and people feeling left out. It makes it fertile ground for stories involving crimes. And that’s before you even get to the physical beauty and geographic diversity — ocean, mountains desert — that is marred by man and nature. Any minute there can be a social or tectonic earthquake. No wonder writers are drawn here.

BNR: If I could broaden that question of geography, what do you think it is that unites crime writers in various countries? For instance, we’ve been seeing a lot of writers from Scandinavia in the past few years. What do you think they share with their American counterparts?

MC: That’s a difficult question to answer, because for the most part I avoid classifying writers by genre or geography. In terms of writing and writers I don’t see a great difference between what somebody is doing in, say, Edinburgh, and what I am doing with L.A. We are writing character-driven stories where the stakes are high and the protagonists must stand strong against dark forces. I think there are of course vogues in reading that result in popularity like the recent Scandinavian explosion. But the beauty of it is that readers are always reading. There’s nobody out there who only reads Scandinavian readers. Nobody who only reads California writers. That would be crazy.

BNR: A question I like to ask the crime writers I get to talk to: Do you think it’s fair to say that contemporary fiction has largely abandoned the task of writing about our primary institutions of justice, and how do you think crime writers have risen to the task?

MC: That’s more classification. I think crime fiction is contemporary fiction. For good or bad, it is hard to write something that is reflective of the world we live in without some mention of crime. The Bonfire of the Vanities is a great American novel, but it’s also about a crime and a court case. So I don’t see the walls between all of these things. But to your point about crime writers, I do think that people writing series fiction are for the most part prolific and contemporary which gives them perhaps the inside track on being able to be reflective on current events and society. There is an importance to that. I feel like it’s the crime writers who are on the ground and reporting from the front lines of society, while the literary writers will be offering their take in five or six years.

BNR: What are the pleasures and challenges of writing about a character for as long as you’ve now written about Harry?

MC: Part of the writing process is getting to know your characters and so there is a great comfort in knowing characters like Mickey Haller and Harry Bosch so well. The challenge is to avoid being static from book to book. You always have to dig deeper and reveal new material. If you fail to do that you’re dead in the water.

BNR: In the acknowledgements to The Black Box you talk about the inspiration of the music of Frank Morgan and Art Pepper (both of whom spent time in prison due to their addictions). Can you talk about that inspiration? Do you write to music or do you need silence to write?

MC: I don’t always have music on, but I do think it’s important in the writing process. I often listen to what Harry listens to while writing those books. It’s a weird thing because the reader obviously can’t hear the music. They only get the reference on the page. But music can be used to say a lot about character. Harry listens to musicians who had to struggle and overcome to make their music. He’s had to struggle and overcome, too. That’s the connection.

BNR: Are you conscious of ways in which your writing or your process has changed over the years? Has it become easier, or does writing become more demanding as you become more experienced?

MC: For any aspect that gets easier there is always going to be something that gets more difficult. I think the biggest change within me is that I have much more confidence in what I can do. So I don’t panic if it is not going well or if I am getting a slow start on a book. I know it will eventually come.

BNR: A softball: If we could see your current “to read” stack, what books in it are you looking forward to most?

MC: Tatiana by Martin Cruz Smith. I have been an Arkady Renko fan since Gorky Park. After that, Cross My Heart by James Patterson. It’s been twenty years of Alex Cross. I know how difficult it is to keep a character alive that long. These two authors have done it and I think I will read these books as much for the lesson as the pleasure.