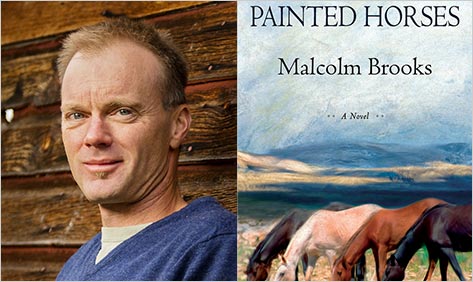

Montana Myths: Malcolm Brooks

It comes as little surprise to learn that Lonesome Dove is a seminal literary influence in Malcolm Brooks’s life. Reading his debut novel, Painted Horses, you’ll hear the voice of Larry McMurtry, as well as echoes of Jim Harrison, Wallace Stegner, and that old go-to, Cormac McCarthy. But make no mistake, Malcolm Brooks stands on his own without leaning on the crutches of those other seasoned writers. Painted Horses — which is a Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers selection and a No. 1 Indie Next Pick for August — is unlike any “western” I’ve read; it refreshes the genre while nodding back at its roots.

It comes as little surprise to learn that Lonesome Dove is a seminal literary influence in Malcolm Brooks’s life. Reading his debut novel, Painted Horses, you’ll hear the voice of Larry McMurtry, as well as echoes of Jim Harrison, Wallace Stegner, and that old go-to, Cormac McCarthy. But make no mistake, Malcolm Brooks stands on his own without leaning on the crutches of those other seasoned writers. Painted Horses — which is a Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers selection and a No. 1 Indie Next Pick for August — is unlike any “western” I’ve read; it refreshes the genre while nodding back at its roots.

Set in Montana in the mid-1950s, the novel presents us with an American West on the cusp of change. Catherine Lemay is a young archeologist hired to survey a canyon in advance of a major dam project; her job is to make sure nothing of historic value will be lost in the coming flood. The task proves to be more complicated than she thought — especially after she meets John H, a mustanger and a veteran of the U.S. Army’s last mounted cavalry campaign, who’s been living a fugitive life in the canyon. Together, the two race against time to save the past before it is destroyed by an industry with an eye on the future.

I met Malcolm at a coffee shop in downtown Missoula, Montana, the city he’s called home for the past two decades. The dimly lit espresso joint was nearly vacant at midday, but Malcolm and I filled the place with vibrant conversation about horses, western literature, and the various jobs he’s held over the years, including stints as a writer for an outdoors television show and, primarily, as a carpenter. He explained how he used his time during the winter off-season to write Painted Horses over the course of about ten years. – David Abrams

The Barnes & Noble Review: As a carpenter-slash-novelist, what is your writing schedule like?

Malcolm Brooks: Oh man, I wish I had a set schedule, but I don’t. I keep saying I’ll get one, but it never happens. I have a really high metabolism — I’m really fidgety and have a hard time sitting still for any length of time, so I end up walking around thinking about stuff all day long. When I sit down and focus on something, I tend to produce in bursts. In carpentry, we typically have these down times between December and March, and so what I’d do every year was sock enough away in my head in order to have this four-month window to just be able to sit there and work lots of ten-hour writing days. I’d take a nap in the middle of it or take the dogs for a walk, but then just keep going. I don’t know how sustainable a working method that is, but I’ve managed to do it so far.

BNR: Were you working on Painted Horses all this time?

MB: I started researching this novel in earnest in 2004, but like most every author I know, I already had three or four other complete novel manuscripts that got shelved. I first thought about becoming a writer in high school when I wrote a straight-up pulp western. Over the years, I tried doing everything from a Larry McMurtry–style coming-of-age novel like The Last Picture Show to wanting to be this black humorist like Vonnegut or McGuane. None of it was really me. Finally, I hit my thirties and I said, “All right, I’ve been doing this a long, long time. I need to figure out what kind of a writer I am. I need to go big or go home.”

BNR: So, after those earlier abandoned novels, what was it that spurred you to start writing this particular book?

MB: The whole springboard for it was the U.S. Army’s ad hoc cavalry in World War Two during the Italian campaign. When I was about twenty or so, I was working for my dad’s small construction outfit in northern California. We did some remodel work on a place, and the owner was this Army veteran who had nothing better to do than hang out on the job site all day long. I tend to be a guy who sits around birthday parties or wedding receptions talking to old people when nobody else wants to. Over the years, I’ve heard some pretty amazing stories. Like this client of my father’s — we started talking with each other, and he found out I was interested in horses. One day he said, “You know, I was part of the U.S. Army’s last mounted cavalry campaign during World War Two in Italy.” Even as a kid, I was going, “Wow!” I just sort of tucked it away as an interesting, little-known fact; and then years and years later, when I was trying to find myself as a writer, I untucked that story of his from the back of my head. I decided to write something about that last Army cavalry campaign. I wanted it to be big and epic, but not cheesy.

BNR: So did Painted Horses start off as a war novel?

MB: At first, I didn’t quite know what it was going to be. I knew I wanted it to be a big, sweeping love story — so there had to be a female, and there had to be this guy who was in the cavalry, but I also wanted it to be a western. So I started thinking, Okay, what if I use the horse cavalry as his back-story and as subtext, but the actual story is something that’s going on now. That will give me a way to explore the past. I got to the point where I wrote a list and asked myself, What are all the things I’m really interested in that haven’t been written about before and don’t necessarily seem to be of a piece, but how are they of a piece within the weave of my own life? What is it that makes me interested in all these seemingly disparate things? So I wrote this list — the Lascaux caves were one thing, the Basques were another, and then there was my long-standing interest in mustangs and Plains Indians. How I landed on the canyon and the archaeology is completely lost to me at this point because it was ten-plus years ago that I was cooking all this stuff up. Anyway, I had all this stuff I was throwing into the blender. I knew I wanted to have horses in it somehow because they’re these totemic, emblematic things that run through the human psyche. You can turn them into a metaphor for all kinds of things. I knew about the mustangs that roam the Pryor Mountains south of Billings, Montana. I knew they were this genetically very distinct band of wild horses, going back to colonial Spanish horses, and I thought, well, that’s what I should use as a model because they crossed time in their original form somehow and there’s something really magical and mysterious about that. As soon as I started researching the Pryor Mountain herd, I learned they’d been displaced by the Yellowtail Dam built across the Bighorn River in the mid-1960s. I thought, All right, there you go. Let’s do something with a dam project and we’ll have a female character who is passionate, driven, and accomplished.

BNR: Catherine Lemay is certainly driven as she embarks on this River Basin Survey project, sponsored by the Smithsonian. I’d never heard of these before reading Painted Horses —

MB: Neither had I until I’d completed the first draft of the novel.

BNR: Really? That’s astonishing to me because it seems like the whole book is centered on the survey.

MB: Well, I knew there was an official policy in place to do archeological surveys, but I could never nail down the actual mechanism, agency, or institution governing them. Much of the initial research for Painted Horses happened in 2004 and 2005, before the Web was totally in flower. A few years later, a general Google search would more readily turn up references to River Basin Surveys, but for quite a while I wrote without fully understanding the historical basis of the basic plot. Eventually, not unlike archaeology, the dots did connect. The thing that tipped me off to the surveys was this rinky-dink little historical society pamphlet from 1962 in which there’s a mention of trying to get volunteers in Wyoming to go work on some of these water reclamation archaeological surveys. They mention River Basin Surveys in conjunction with Bighorn Canyon and the Yellowtail Dam. I thought, Okay, that has to be a real thing, so I started to Google around for that, and then found these old, in-house records and publications and was able to get some of those through used bookstores.

BNR: Against this broader political and environmental backdrop, you develop this fascinating relationship between a wounded, taciturn cowboy named John H and the brave, but relatively naïve, Catherine. How did you balance their love story against what you admit is a big, sweeping epic? How do you as a writer keep sight of the comparatively small person against the large canvas of a Western landscape?

MB: I’ve always been drawn to stories in which the lives of regular people are thrown up against huge historical events — The Unbearable Lightness of Being, for example, or The Last of the Mohicans. The world spins and history unfolds, but the people caught in the gravitational pull of outsized circumstances still have to eat and breathe and yearn and fall in love. I think I tend without really thinking about it to treat the “large canvas” as part of the setting, but focus most of my energy on breathing as much life as I can into the characters. I love writing dialogue, for example, that on the surface doesn’t seem to have much to do with plot or crisis. Characterization comes first, I guess. Also, nothing’s as dramatic as a really intense love affair, at least to the people involved, even if — or maybe especially if — such a thing unfolds with bombs going off in the background.

BNR: We never learn John H’s last name — one character speculates it stands for “horse.” Why did you make that choice as a writer?

MB: I wanted him to have an air of eternal mystery, to be a sort of enigmatic yet almost timeless figure. Originally his name was going to be John Henry, as a sort of obvious nod to the folk legend. As I made notes in advance of the actual writing, I kept abbreviating his name to John H, and realized it just had a sort of mysterious ring to it, and that it looked sort of lovely on the page as well.

BNR: Dub Harris, the dam contractor, makes no bones about his intentions and feelings about the canyon as he writes to Catherine in a letter: “By modern reckoning the canyon is a wasteland and I intend to drown it.” In literature, it’s easy to paint big corporations with a broad brush as greedy and evil, but you manage to put the company building the dam in a gray light — neither completely black nor completely white.

MB: Look, I’m hyper-aware of the fact I wouldn’t have the luxury of sitting at a computer working on a novel in an attempt to carve my own destiny, without the instant results of the power outlet or the light switch or the antibiotics I’ve taken over the years, which in the case of the latter have literally kept me alive to this point. None of that happens in a vacuum. It’s pretty unfashionable in literary circles to mention Ayn Rand in a way that isn’t predicated on withering contempt, but the fact of the matter is, whatever her excesses or absolutism or chilling implications, she got it right when she said that Nature is less a Rousseauist paradise than it is a seething, amoral, heartless bitch (takes one to know one!), with no care or consideration for the individual. Again, it’s a supreme duality — Dub Harris may be a bastard, but he’s a damned useful one.

BNR: You mentioned earlier that horses can be malleable as literary symbols. What role do you see the mustangs playing in the novel? Are they a symbol of the dying Old West in the face of post-war industrialism? Or is it something more complex than that?

MB: Partially a symbol of that, but the figure of the horse as a totem in the human consciousness long antedates either the mustang or the American West. To me, the human alliance with the horse parallels the invention of art and symbolic or ritualistic myth — John H. in a sense is a sort of extended metaphor for the presence and importance of the horse as both a real and a mystical vehicle, in an archetypal way.

BNR: I felt like Painted Horses itself is an attempt to reinvent the archetype of the American western. To what degree do you as a writer stand with one foot in the tradition of Larry McMurtry and John Ford but yet write something fresh for modern readers?

MB: Painted Horses certainly has one foot, deliberately, in the western romantic tradition, but also one foot very definitely in something much more expansive. The traditional western was passé nearly as quickly as the trail-drive era of the West itself, which gave us most of its clichés and tropes. But the power of the myth still has enough to currency to keep it alive as a major cultural touchstone, not only here, but also around the world. Interestingly, you cite two examples that, at least to me, parallel my own effort in an operative sense — John Ford and Larry McMurtry both nod to and valorize the romantic tradition on the one hand, while often balancing or subverting it on the other. The Searchers and Lonesome Dove are both major influences on me, just in terms of literary or thematic sensibility. I think my greatest strengths in terms of bending or reinventing the genre are probably that I tend to see the western frontier experience itself as beginning not with Lewis and Clark 200 years ago but with the Bering Land Bridge and the arrival of mammoth hunters 12,000 years ago. In other words, I see it as a chapter in a much older, much more formative human drama. Also, while I’m not a straight-up, iconoclastic revisionist, I think I am a cultural relativist — I don’t believe in simplistic morality plays or black hat–white hat clichés, but I do accept and even court the spiritual power of myth, including the myth of the West.