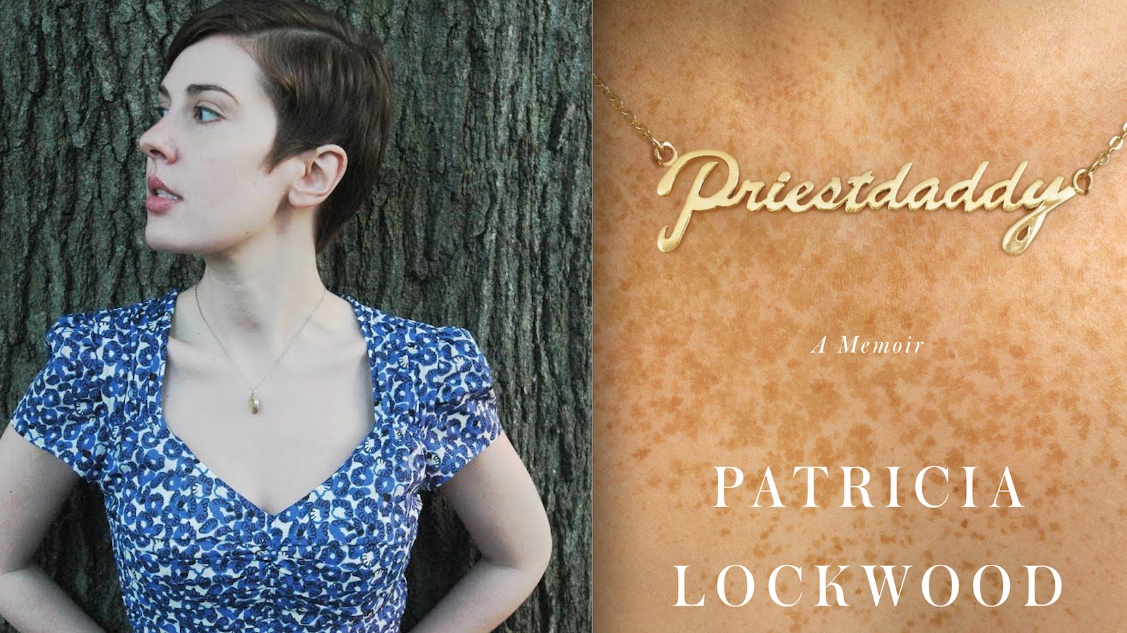

Patricia Lockwood Finds Her Calling

Patricia Lockwood may have a fraught relationship to Catholicism, but she’s sure that the Church made her a better writer. “It is one of the richest sources of language that we have. If you go through the first twenty years of your life as a Catholic and you can’t string together a decent metaphor, you’re fucked.”

Reading Priestdaddy, Lockwood’s memoir about the year she and her husband moved back home to live with her father, a guitar-playing, sports car–driving Catholic priest, is like watching the English language being born again. At turns funny, absurd, and heartbreaking, Lockwood’s observations about her family, the cultlike youth group she attended as a teenager, and the scandals within the Church are told with an inventiveness that brings even the most mundane details to life. When asked by her husband what a seminarian is, for instance, Lockwood offers, “an unborn priest, who floats for nine years in the womb of education, and then is finally born between the bishop’s legs into a set of exquisite robes.”

The book does not shy away from more serious topics, particularly the frequent cover-ups of sexual abuse committed by both the priests and the male parishioners in Lockwood’s community. But Priestdaddy may also complicate secular readers’ assumptions about the religious Right. While Lockwood experienced a childhood of repression and constriction, especially in relationship to her body and her role as a woman, she was also afforded a surprising amount of freedom, particularly around art and writing, that may not have existed outside of the Church.

I spoke with Lockwood during her trip to London about the similarities between artists and priests, the power of being genderless, and how to write your way into your body. —Amy Gall

The Barnes & Noble Review: Do you think there are similarities between the calling of the artist and the calling of the priest?

Patricia Lockwood: I totally think so. I think you have to have something special inside you to decide that you even feel that call. You do wonder, is it a presumptuous thing to decide that you’ve been called to these particular lives? When you are a writer, how is it that you know that you are being called to be “the voice”? That’s a big thing. That requires either some narcissism, some very healthy self-belief, or it’s a real calling. I think it must have been that way for my father as well; something about his calling was external, like something inside of him was flowing toward some other purpose. And that’s how it feels for me. I wonder if I would have had such faith that I was absolutely meant to be a writer if I hadn’t seen that example.

BNR: Corruption aside, I felt almost jealous of the ceremony surrounding Catholicism. Art doesn’t have those kinds of clear, outside markers of achievement built into it.

PL: I know! Wouldn’t it be great if a mantle just descended upon us? A difference I’ve noticed between myself and other women of my age is that a lot of them talk about having impostor syndrome, and I never, ever had that, to the point where I wondered if I was abnormal. And then I thought, Well, look at your dad and the position you are in and the and the example you had of how one could move through life, and I thought, Well, it makes sense then that I wouldn’t ever question it.

BNR: Do you think that’s an empowering aspect of religion?

Priestdaddy

Priestdaddy

Hardcover

$16.61

$27.00

PL: Maybe so. Or maybe it means that I’m deluded. With writing it’s the kind of thing that other people get to decide. I can say that I feel this calling, but if what I produce doesn’t speak to people in some way, my calling doesn’t mean shit. But part of the feeling of having the calling is that other people’s experience of my work is also beside the point. I did always expect that I would be read, but it also feels like even if I weren’t read, I’d continue to write. I’ve always thought that my assurance as a writer is more male, in a socialized sense.

BNR: It’s interesting, because you are also grappling in this book with the really restrictive aspects of growing up Catholic and female, and how that affected your sense of your body.

PL: And maybe if you receive those sorts of messages about your body and about what it means to be a woman, one way to free yourself of that is to just never think about being a woman at all, to take some sort of third road. I mean, gender has always been such a particular and interesting question for me. I never feel female. In my mind, I’m just some unsexed spirit flying by. And it’s hard to know if that is even to do with my feelings about my own gender or if it’s just about avoiding the extreme, oppressive role that you are raised to inhabit if you are a female in the Catholic Church. I think to get around that oppression I thought of myself as being neither male nor female.

BNR: Do you think that writing about yourself so intimately in this book has brought you closer to your body?

PL: The body has always figured very largely and viscerally in my work, but as I said, I largely always feel very unsexed. But if you look at my metaphors as far back as it goes, I’m always writing about the body in a very specific way.

BNR: Do you feel in your body when you write?

PL: No. I feel like a cloud with a bird in the middle of it.

BNR: Gender is such a hard thing to define for yourself, and the body can sometimes contradict what you think about your gender in your head.

PL: Yeah, and it can make you feel pinned down. And it forces you to consider things you don’t want to think about as this spirit of the air who is just pure idea. And I don’t know if that’s a function of being raised in the Catholic Church, where we talked so much about the body and there were these images everywhere you looked of the body suffering and in pain. In my household, you were constantly coming up against the limits of the body, and I just wanted to float above it. Catholic thinking is so centered in the body, specifically in its agonies and to some extent its ecstasies, but it’s hard to not feel hemmed in by it.

BNR: You talked about observing pregnant Catholic women in your community, and that seemed liked a deeply bodied, ecstatic experience as well.

PL: It felt like you were at the center of biology. There was a happiness to these women, too, that had to do with giving yourself over to the cycle of life. And in a lot of cases, the body wants to be pregnant — nature dictates that if you don’t take certain precautions you will have a lot of kids. So there was this very interesting air of handing yourself over to nature, which to them was God. It was interesting to be part of that and not know if I wanted children or if I would be a good mother or that sort of thing. I imagine you would find a similar thing in Orthodox or Mormon populations, but it’s very specific and hard to describe to people outside of those communities who haven’t experienced it.

BNR: It seems, because women are so sidelined in Catholicism, being pregnant is also a way of being centered and powerful.

PL: Absolutely. You almost want to say it’s about status, but it’s about power and power in neither a negative or positive sense but simply a way of taking up space. If you believe, as the seminarian told me in the book, that “women are the tabernacle of life,” of course that makes you, as a pregnant woman, important. And people may look at Catholic women with tons of kids from the outside and think, Oh, these poor, oppressed women, but of course that’s not what people’s experiences of their own lives are. And I wanted to show that.

BNR: Was it difficult, as an adult, to observe your family and the Church, or did that feel like a natural role for you to play?

PL: It felt very hard to be back in my family home and back at the center of Catholicism, so much so that I disassociated. I so did not want to be in my body as I was undergoing these conversations, and when I was in the church talking to parishioners, it’s almost like I fled outside myself into this place of observation. And maybe that is what I’m talking about when I talk about my experience of genderlessness as a child and a teenager. Maybe it is that disembodied place where you are just a pure eye.

But now, having gone through that, I would say I feel better disposed or more comfortable with owning the fact that I am Catholic, at least culturally. When you leave the house or leave a religion, there is probably a period of anger that can last for a while. But going back in and considering things as an adult, I didn’t want to take people’s religious feelings lightly. Because Catholicism is true for those people, it is the Gospel and it dictates how they live their lives.

BNR: You said of the Catholic Church, “The question for someone who was raised in a closed circle and then leaves it, is what is the us, and what is the them, and how do you ever move from one to the other?” Do you think you’ve answered that question?

PL: I think I’ve seen for myself how difficult it actually is to answer a question like that. Even when I was writing the book I still felt like I was under the jurisdiction of these people. I found it very difficult to put down anything that might enrage someone or that someone would find too revealing. I was still thinking about what was considered a secret and not a secret on [the Church’s] terms. And in that sense I think you always still belong to the circle, in that your first instinct is to close the shape and protect the other people and what’s within. But I don’t think everyone feels that way. I think my experience [of feeling protective of the circle] was maybe more intense in that regard.

BNR: You do confront the abuses of power, particularly the sexual abuses that took place within the Church. How did you decide what to tell and what not to tell?

PL: There are definitely things that are not in the book that I did not put in there because they were not mine. And there were other things that might have happened to a friend of mine that shed a much wider light on what’s going on in the Church, and I had to think, Do I put that in? Do I make her anonymous? So, on a case-by-case basis, I had to make those decisions. If it felt like it was necessary to the story, then it went in.

And the question of what’s mine to tell is an effective question of the modern moment. It’s not something the New Journalism was considering in the ’60s and ’70s. But now, I see a lot of young women grappling with what is theirs to talk about. I don’t see it so much among men. But there have also been many cases lately of high-profile stories written by men that blew up because they revealed things that shouldn’t have, and they realized in the wake of it that they’d made a mistake. So maybe men will start considering ownership, more out of their own self-protection if nothing else.

BNR: In the book you talk a lot about the struggle to believe in yourself and trust your own instincts. Do you think writing the book strengthened your sense of self?

PL: I think it did. While I never had any doubts about myself as a writer, it was impossible for me to write about myself. I always had this voice in my head when I wrote about myself, questioning whether I was telling the truth. With my father, when he yelled at me as a child, he would say that I was not being truthful, to the point where I would begin to doubt my own words even when I was being truthful. So I had a difficult time setting down the most basic facts about myself, even saying, ‘Today I felt happy, today I felt sad.” I just questioned if that was true. And I think, writing a book where I had to do that on every page probably did help to strengthen my sense of self.

But that might be why I also have such a hyperbolic and outrageous voice as well, because if no one believes you, are free to say anything that you want.

BNR: This book made me feel drunk with word joy. What is your favorite thing about language?

PL: Its flexibility. I almost said malleability but that’s not exactly right. I think of it more like a body, like a gymnast springing and doing back handstands. There are these rigid rules, there is a skeleton, there are laws by which language abides, but within that there’s such movement.

I also love the rigidity of language. I was always one of those enforcers who spelled really well and had this innate sense of grammar. I was a real prescriptivist when I was younger. And part of that is just being an asshole. Everyone is a prescriptivist when they are teenagers. But I think I was more of an asshole than most.

But with this book I get to break the rules and stay within them at the same time. It’s like my father; he has the desire to lie down with the rulebook so he can feel safe, but at the same time, he is this outrageous character who also wants to exist lawlessly, flying by in a motorcycle. It’s the same with me.

PL: Maybe so. Or maybe it means that I’m deluded. With writing it’s the kind of thing that other people get to decide. I can say that I feel this calling, but if what I produce doesn’t speak to people in some way, my calling doesn’t mean shit. But part of the feeling of having the calling is that other people’s experience of my work is also beside the point. I did always expect that I would be read, but it also feels like even if I weren’t read, I’d continue to write. I’ve always thought that my assurance as a writer is more male, in a socialized sense.

BNR: It’s interesting, because you are also grappling in this book with the really restrictive aspects of growing up Catholic and female, and how that affected your sense of your body.

PL: And maybe if you receive those sorts of messages about your body and about what it means to be a woman, one way to free yourself of that is to just never think about being a woman at all, to take some sort of third road. I mean, gender has always been such a particular and interesting question for me. I never feel female. In my mind, I’m just some unsexed spirit flying by. And it’s hard to know if that is even to do with my feelings about my own gender or if it’s just about avoiding the extreme, oppressive role that you are raised to inhabit if you are a female in the Catholic Church. I think to get around that oppression I thought of myself as being neither male nor female.

BNR: Do you think that writing about yourself so intimately in this book has brought you closer to your body?

PL: The body has always figured very largely and viscerally in my work, but as I said, I largely always feel very unsexed. But if you look at my metaphors as far back as it goes, I’m always writing about the body in a very specific way.

BNR: Do you feel in your body when you write?

PL: No. I feel like a cloud with a bird in the middle of it.

BNR: Gender is such a hard thing to define for yourself, and the body can sometimes contradict what you think about your gender in your head.

PL: Yeah, and it can make you feel pinned down. And it forces you to consider things you don’t want to think about as this spirit of the air who is just pure idea. And I don’t know if that’s a function of being raised in the Catholic Church, where we talked so much about the body and there were these images everywhere you looked of the body suffering and in pain. In my household, you were constantly coming up against the limits of the body, and I just wanted to float above it. Catholic thinking is so centered in the body, specifically in its agonies and to some extent its ecstasies, but it’s hard to not feel hemmed in by it.

BNR: You talked about observing pregnant Catholic women in your community, and that seemed liked a deeply bodied, ecstatic experience as well.

PL: It felt like you were at the center of biology. There was a happiness to these women, too, that had to do with giving yourself over to the cycle of life. And in a lot of cases, the body wants to be pregnant — nature dictates that if you don’t take certain precautions you will have a lot of kids. So there was this very interesting air of handing yourself over to nature, which to them was God. It was interesting to be part of that and not know if I wanted children or if I would be a good mother or that sort of thing. I imagine you would find a similar thing in Orthodox or Mormon populations, but it’s very specific and hard to describe to people outside of those communities who haven’t experienced it.

BNR: It seems, because women are so sidelined in Catholicism, being pregnant is also a way of being centered and powerful.

PL: Absolutely. You almost want to say it’s about status, but it’s about power and power in neither a negative or positive sense but simply a way of taking up space. If you believe, as the seminarian told me in the book, that “women are the tabernacle of life,” of course that makes you, as a pregnant woman, important. And people may look at Catholic women with tons of kids from the outside and think, Oh, these poor, oppressed women, but of course that’s not what people’s experiences of their own lives are. And I wanted to show that.

BNR: Was it difficult, as an adult, to observe your family and the Church, or did that feel like a natural role for you to play?

PL: It felt very hard to be back in my family home and back at the center of Catholicism, so much so that I disassociated. I so did not want to be in my body as I was undergoing these conversations, and when I was in the church talking to parishioners, it’s almost like I fled outside myself into this place of observation. And maybe that is what I’m talking about when I talk about my experience of genderlessness as a child and a teenager. Maybe it is that disembodied place where you are just a pure eye.

But now, having gone through that, I would say I feel better disposed or more comfortable with owning the fact that I am Catholic, at least culturally. When you leave the house or leave a religion, there is probably a period of anger that can last for a while. But going back in and considering things as an adult, I didn’t want to take people’s religious feelings lightly. Because Catholicism is true for those people, it is the Gospel and it dictates how they live their lives.

BNR: You said of the Catholic Church, “The question for someone who was raised in a closed circle and then leaves it, is what is the us, and what is the them, and how do you ever move from one to the other?” Do you think you’ve answered that question?

PL: I think I’ve seen for myself how difficult it actually is to answer a question like that. Even when I was writing the book I still felt like I was under the jurisdiction of these people. I found it very difficult to put down anything that might enrage someone or that someone would find too revealing. I was still thinking about what was considered a secret and not a secret on [the Church’s] terms. And in that sense I think you always still belong to the circle, in that your first instinct is to close the shape and protect the other people and what’s within. But I don’t think everyone feels that way. I think my experience [of feeling protective of the circle] was maybe more intense in that regard.

BNR: You do confront the abuses of power, particularly the sexual abuses that took place within the Church. How did you decide what to tell and what not to tell?

PL: There are definitely things that are not in the book that I did not put in there because they were not mine. And there were other things that might have happened to a friend of mine that shed a much wider light on what’s going on in the Church, and I had to think, Do I put that in? Do I make her anonymous? So, on a case-by-case basis, I had to make those decisions. If it felt like it was necessary to the story, then it went in.

And the question of what’s mine to tell is an effective question of the modern moment. It’s not something the New Journalism was considering in the ’60s and ’70s. But now, I see a lot of young women grappling with what is theirs to talk about. I don’t see it so much among men. But there have also been many cases lately of high-profile stories written by men that blew up because they revealed things that shouldn’t have, and they realized in the wake of it that they’d made a mistake. So maybe men will start considering ownership, more out of their own self-protection if nothing else.

BNR: In the book you talk a lot about the struggle to believe in yourself and trust your own instincts. Do you think writing the book strengthened your sense of self?

PL: I think it did. While I never had any doubts about myself as a writer, it was impossible for me to write about myself. I always had this voice in my head when I wrote about myself, questioning whether I was telling the truth. With my father, when he yelled at me as a child, he would say that I was not being truthful, to the point where I would begin to doubt my own words even when I was being truthful. So I had a difficult time setting down the most basic facts about myself, even saying, ‘Today I felt happy, today I felt sad.” I just questioned if that was true. And I think, writing a book where I had to do that on every page probably did help to strengthen my sense of self.

But that might be why I also have such a hyperbolic and outrageous voice as well, because if no one believes you, are free to say anything that you want.

BNR: This book made me feel drunk with word joy. What is your favorite thing about language?

PL: Its flexibility. I almost said malleability but that’s not exactly right. I think of it more like a body, like a gymnast springing and doing back handstands. There are these rigid rules, there is a skeleton, there are laws by which language abides, but within that there’s such movement.

I also love the rigidity of language. I was always one of those enforcers who spelled really well and had this innate sense of grammar. I was a real prescriptivist when I was younger. And part of that is just being an asshole. Everyone is a prescriptivist when they are teenagers. But I think I was more of an asshole than most.

But with this book I get to break the rules and stay within them at the same time. It’s like my father; he has the desire to lie down with the rulebook so he can feel safe, but at the same time, he is this outrageous character who also wants to exist lawlessly, flying by in a motorcycle. It’s the same with me.