Philip Larkin: Life, Art and Love

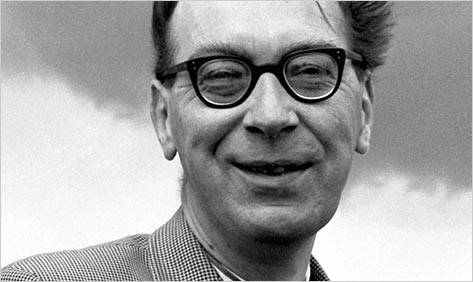

Outside of his poetry — and, for the most part, within it — Philip Larkin presented to the public a mild, modest façade. He made a career as a responsible, dedicated, even talented librarian, and his quiet, self-effacing demeanor seemed to adhere more to the stereotypes attached to that profession than to those that govern our expectations of poets. After a liberating stint in Belfast, away from his family, he settled in the English city of Hull, living there from 1955 until the end of his life in 1985. “It is a little on the edge of things,” he said of Hull. “I rather like being on the edge of things.” Larkin traveled little, made few public appearances, regarded the fame that eventually came to him with bemused skepticism, and mostly stayed home, polishing his precise and perfect poems, doing his own laundry, and (you likely could have guessed this part) composing letters to his mother.

Outside of his poetry — and, for the most part, within it — Philip Larkin presented to the public a mild, modest façade. He made a career as a responsible, dedicated, even talented librarian, and his quiet, self-effacing demeanor seemed to adhere more to the stereotypes attached to that profession than to those that govern our expectations of poets. After a liberating stint in Belfast, away from his family, he settled in the English city of Hull, living there from 1955 until the end of his life in 1985. “It is a little on the edge of things,” he said of Hull. “I rather like being on the edge of things.” Larkin traveled little, made few public appearances, regarded the fame that eventually came to him with bemused skepticism, and mostly stayed home, polishing his precise and perfect poems, doing his own laundry, and (you likely could have guessed this part) composing letters to his mother.

His considerable reputation as a poet rested on a slim corpus. During his lifetime his poems appeared in four full-length volumes: The North Ship (1945), The Less Deceived (1955), The Whitsun Weddings (1964), and High Windows (1974). The first is apprentice work, pleasant but mostly unremarkable. All four are very modest in length. When a Collected Poems appeared in 1988, edited by Larkin’s friend Anthony Thwaite, many were surprised by how large a book it was; Thwaite had added a large number of unpublished poems or poems that had not been collected in the “official” volumes. He had also, controversially, organized the poems by date of composition, an act of daring about which some literary scholars are still prone to lose sleep.

There were other surprises in store, and more controversies to come. Larkin thought a lot about sex, as it turns out, wrote about it in his letters, and talked about it to his friends and coworkers, sometimes in terms that were, one presumes, not entirely in line with accepted standards of professional conduct. James Booth, in his new biography of Larkin, relates that at the University of Hull,

[t]he Librarian’s office was on the ground floor overlooking a huge sunken lawn known as the “soup-plate.” Betty [Mackereth, Larkin’s secretary] recalls that in the summer Larkin would hold a lens in each hand and adjust them at different distances from his eye to view the women students lying around in the sun. Playing astutely on his youth he allowed his own romantic affections to become the subject of collective interest among his staff, and dramatized his lusts for particular students. One such student, Maeve [Brennan] remembers, “was of Amazonian build — Philip entertained a fantasy about well-proportioned women — and he named a tiny room in the new Library after her, where, the idea was, he would be able to seduce her.” For a time this was known as “Miss Porter’s room.”

It was of course a different age; such behavior by a university librarian would likely not be so kindly looked upon now. Larkin also had an interest in pornography, including, it seems, some violent and bondage-themed pornography; after his death his solicitor, Terry Wheldon, removed two large cardboard boxes of it from his residence, so as not to leave the bereaved to deal with and be disturbed by it. (It was, it appears, a courtesy Wheldon provided to many of his clients.) Larkin shared his enthusiasm for pornography with his friends Kingsley Amis and Robert Conquest; his letters to them contain numerous sexist remarks. They are also racist, in multiple places, or at the very least they appear to be. Indeed, reading the selection of his letters published in 1992, one begins to feel that the Larkin who pined for the glory days of the Empire was pining, in part, for the era when England was something close to a whites-only club.

It was of course a different age; such behavior by a university librarian would likely not be so kindly looked upon now. Larkin also had an interest in pornography, including, it seems, some violent and bondage-themed pornography; after his death his solicitor, Terry Wheldon, removed two large cardboard boxes of it from his residence, so as not to leave the bereaved to deal with and be disturbed by it. (It was, it appears, a courtesy Wheldon provided to many of his clients.) Larkin shared his enthusiasm for pornography with his friends Kingsley Amis and Robert Conquest; his letters to them contain numerous sexist remarks. They are also racist, in multiple places, or at the very least they appear to be. Indeed, reading the selection of his letters published in 1992, one begins to feel that the Larkin who pined for the glory days of the Empire was pining, in part, for the era when England was something close to a whites-only club.

Again we must say: it was a different age. Such sentiments were not at all unusual in Larkin’s social context, and his objectifying views of women, and fear of them, were in part reflections of and in part reactions against the rigid and stultifying system of middle-class expectations that shaped English life during that period. Larkin fought his whole life to evade the perceived requirements of conventional middle-class existence; skittish even of minor commitments, he did his best to avoid, as he put it in a letter to James Sutton, “furniture and loans from the bank.” Along with them, he avoided both marriage and, for the most part, monogamy. For much of his life he carried on simultaneous romantic relationships with his colleague Maeve Brennan and with Monica Jones, a university lecturer at Leicester. Brennan, who was traditional and Catholic, hoped he would marry her; Jones, whose more modern sensibility shared some of the resistance Larkin felt toward the institution of marriage, was more ambivalent. A handful of other women also formed romantic attachments with the poet, some of which overlapped with Jones’s and Brennan’s. The most significant, perhaps, was another colleague, Betty Mackereth, Larkin’s secretary at the University of Hull. Their affair did not become known to either Jones or Brennan until after Larkin’s death.

The complications of Larkin’s personal life found their way, inevitably, into the poems. Some of them are love poems, directed toward various beloveds. The lovely “Broadcast,” for example, has Larkin listening, on the radio, to a concert that Monica Jones is attending in person, partly as a way of making contact with her; the poem is addressed to her, and the end of the musical program leaves him “desperate to pick out / Your hands, tiny in all that air, applauding.” “Self’s the Man” begins with Larkin comparing his bachelorhood, favorably, to an imagined married man:

Oh, no one can deny

That Arnold is less selfish than I.

He married a woman to stop her getting away

Now she’s there all day,And the money he gets for wasting his life on work

She takes as her perk . . .

though it ends on a note of characteristic Larkinesque doubt:

So he and I are the same,

Only I’m a better hand

At knowing what I can stand

Without them sending a van —

Or I suppose I can.

But could he? The messiness of his personal life — hinted at but not made fully manifest in the poems — surely caused both inconvenience and a not insignificant amount of emotional distress to all the participants, Larkin included. And at least some of his lovers, Maeve Brennan chief among them, felt rather deceived when his letters became available: the crass, rude, rowdy, and raunchy Larkin that kept up a correspondence with Kingsley Amis was not the refined and genteel Larkin she felt she knew. Still, those commentators who saw the posthumous backlash against Larkin, particularly when it focused on his personal romantic attachments, as excessively judgmental and narrow-minded must be acknowledged to have a point. He was, for the most part, not duplicitous, and on the whole seemed to treat his lovers with genuine consideration and care.

The small-minded and offensive political sentiments expressed in his letters ought, perhaps, to disturb us more, though there is always the difficulty of knowing when Larkin was being ironic (he frequently was) and when he was being sincere. He did not intend the letters for wide distribution, and he might well have expected those for whom they were meant to be able to tell the difference. And after all, he did enjoy shocking his readers and could do so to great literary effect; he often did so in his very best poems, as in his deployments of “fuck” in the brutally hilarious “This Be the Verse” (“They fuck you up, your mum and dad” is the famous opening line) and the poignant and chilling “High Windows,” whose first stanza reads:

When I see a couple of kids

And guess he’s fucking her and she’s

Taking pills or wearing a diaphragm,

I know this is paradise

He was a poet, then, who reveled in mixing the high and the low, the sacred and the profane. So why not simply put the issue of personal evaluation aside? Surely the poems are one thing, and the poet another, so that we can take pleasure in the former without making up our minds to approve of the latter? This is an attractive stance, but Booth — whose new biography of Larkin seems intended, in large part, as an exercise in rehabilitation, a book that will make it possible again to admire the poems without turning away from their author — is skeptical of the attempt to separate the two:

There is, of course, no requirement that poets should be likeable or virtuous. But we might ask whether art and life can have been so deeply at odds with each other that the poet who composed the heart-rending “Love Songs in Age,” the euphoric “For Sidney Bechet” and the effervescent “Annus Mirabilis” had no emotions, or was a shit in real life.

One can sympathize with this, up to a point. Art and life are not entirely isolated from each other. It would be surprising, if one knew their poems but nothing about their lives, to be told that Wordsworth did not enjoy the outdoors or that John Berryman was a teetotaler with a low sex drive. On the other hand, while the composition of heartrending and effervescent poems may serve as evidence that the poet was not without emotions, it hardly seems to show he was a likable person or that he was free of racist prejudices. And it would be all too easy to turn Booth’s argument against him just by choosing other poems. Can art and life be so deeply at odds that the poet who composed “Self’s the Man” wasn’t a bit of a misogynist? Can art and life be so deeply at odds that the poet who composed “This Be the Verse” or “Take One Home for the Kiddies” was not, as a matter of fact, kind of a shit in real life?

Booth is right to remind us that some of Larkin’s more outrageous remarks were surely intended ironically, but it is difficult to sympathize with his apparent desire to dismiss every potentially offensive comment in that way. At a certain point one wants to shout “Enough! Surely the man meant it at least some of the time!” Moreover, his overgenerosity extends past the poet himself and to his body of work. Good as they are — and the best of them are quite fine indeed — Larkin’s poems cannot quite live up to the grand claims Booth makes on their behalf. The fact is that to many contemporary readers, they will inevitably come across as a bit stale, a bit staid. Larkin would have regarded such apparent faults as virtues; he had little interest in radical, progressive, or experimental notions of what poetry ought to be, and mostly seemed to look back longingly to a tradition that rejected all of the more radical aspects of literary modernism. But whether by design or not, the effect of this conservative stance is that in comparison with such early twentieth-century modernists as Eliot, Pound, Williams, and Crane — not to mention such contemporaries of Larkin as Allen Ginsberg (whose revolutionary “Howl” was composed and first read in public in 1955, the year The Less Deceived came out) or John Ashbery (whose first book, Some Trees, was published the following year, and whose Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror was published the year after Larkin’s final collection, High Windows) — Larkin’s work can come across as fussy, quaint, perhaps a bit retrogressive.

If Larkin had any curiosity about what was going on in the wider poetry world, there is almost no evidence of it. In fact he often seemed proud of his parochialism. He never tired of complaining about any art that seemed to him remotely avant-garde — Picasso and Finnegans Wake were “crazy”; John Coltrane’s music was “a pain between the ears” — or crabbily pining for the good old days when “painting represented what anyone with normal vision sees, and music was an affair of nice noises rather than nasty ones.” On multiple occasions, moreover, he expressed a principled lack of interest in work written in languages other than English or, at times, in countries other than England. Asked in a Paris Review interview about his fellow poet-librarian, Jorge Luis Borges, he responded, “Who’s Jorge Luis Borges?” Later in that same interview, when asked to compare American with British poetry, he brushes the question aside, stating “I’m afraid I know very little about American poetry.” Near the end of the interview he goes still further, suggesting that even in his home country there is only one poet that interests him: “I’ve never been much interested in other people’s poetry.” And when the interviewer inquires about his previously stated view that he has no curiosity regarding poetry not written in English, he replies,

I don’t see how one can ever know a foreign language well enough to make reading poems in it worthwhile. Foreigners’ ideas of good English poems are dreadfully crude: Byron and Poe and so on. The Russians liking Burns. But deep down I think foreign languages irrelevant. If that glass thing over there is a window, then it isn’t a fenster or a fenêtre or whatever. Hautes Fenêtres, my God! A writer can have only one language, if language is going to mean anything to him.

There is a self-satisfied smallness here that is hard to get past (particularly if, like me, you rather like Byron and Poe), and that runs so deep in Larkin that Booth, for all his efforts, cannot render his subject genuinely likable or even, much of the time, genuinely interesting. Despite the complications of his romantic life, Larkin’s day-to-day existence does not make for compelling reading. Or at any rate it would take a more inspired writer than Booth to make it come across as such. Add this to the facts that multiple biographies of and books about Larkin already exist, that the furor over the poet’s various personal deficiencies seems mostly to have died down some time ago, and that Larkin’s poetic reputation is at any rate stable and secure, and it becomes difficult not to see this new biography as a somewhat unnecessary endeavor.

The overriding impression Philip Larkin: Life, Art and Love leaves one with is that its subject was a small person, and sad. Perhaps Larkin himself, the man who famously said, “Deprivation is to me what daffodils were to Wordsworth,” would not have objected to this depiction. It cannot be denied that death, the ultimate deprivation, was one of Larkin’s great subjects. It inspired some of the most powerful of his poems, including the brilliant “Aubade,” the last major poem Larkin achieved. It was also a kind of obsession for him, providing a deep and pervasive injustice about which to complain, a cosmic villain to rebel against. Even as a young man he seems to have felt the looming and terrifying presence of old age and of what lay beyond old age. In “Age,” a poem from The Less Deceived, he is already, at the age of thirty-three, lamenting, “By now so much has flown / From the nest here of my head that I needs must turn / To know what prints I leave.”

“I don’t want to transcend the commonplace,” Larkin told John Haffenden in 1981. “I love the commonplace. I lead a very commonplace life. Everyday things are lovely to me.” It makes sense that someone who so loved everyday life would cling fiercely to life and fear death so intensely. But by his mid-forties his fear of becoming an old man seems to have helped turn him into one. (His heavy drinking and steadily increasing weight also contributed.) From then on his life slid heavily downhill, both physically and emotionally. “His poetry had become a widely spaced series of ever more subtly successful poems about failure,” Booth observes. After the publication of High Windows he felt that his life as a writer had also reached its end, and he wrote almost nothing, though he lingered for more than a decade, occupying himself in other ways. His mental state in these years must have resembled that described in what is perhaps my favorite of his poems, “Sad Steps,” which begins with the poet “[g]roping back to bed after a piss” and ends with him staring through a window at the moon:

One shivers slightly, looking up there.

The hardness and the brightness and the plain

Far-reaching singleness of that wide stareIs a reminder of the strength and pain

Of being young; that it can’t come again,

But is for others undiminished somewhere.