Picturing Langston Hughes

Readers familiar with the Harlem Renaissance poet, activist, and teacher Langston Hughes may not know about his works for children. But Hughes was at the forefront of the Black Children’s Literature movement of the 1930s. At that time, racist imagery was embedded in many children’s books, which often featured cartoonish picaninnies — child buffoons, raggedly clothed — speaking in a pidgin dialect. The most notorious example was Helena Bannerman’s Little Black Sambo.

Readers familiar with the Harlem Renaissance poet, activist, and teacher Langston Hughes may not know about his works for children. But Hughes was at the forefront of the Black Children’s Literature movement of the 1930s. At that time, racist imagery was embedded in many children’s books, which often featured cartoonish picaninnies — child buffoons, raggedly clothed — speaking in a pidgin dialect. The most notorious example was Helena Bannerman’s Little Black Sambo.

In the 1932 Children’s Library Yearbook, Hughes said that Little Black Sambo exemplified the “pickaninny variety” of the storybook, “amusing undoubtedly to the white child, but like an unkind word to one who has known too many hurts to enjoy the additional pain of being laughed at.” Hughes went on to create works for children to counter the negative imagery, and The Dream Keeper and Other Poems, first published in 1932, was designed for this purpose.

Two-time Caldecott Honor and Coretta Scott King Illustrator Award winner Brian Pinkney has provided scratchboard art for the contemporary reissue of The Dream Keeper. The artist jumped at the opportunity to supply the images, explaining, “I grew up enjoying the poems of Langston Hughes. As a child these depictions of Black life in America offered a mirror in which I could see my own people reflected. When editor Ann Schwartz presented the project to illustrate Hughes’s poems for a new generation of readers, it was like coming home.”

In addition to Pinkney’s excellent volume, two other renowned children’s book artists have chosen to call out a single Hughes poem to illustrate in picture-book format. Charles R. Smith is a renaissance man himself. As a poet, he is the Coretta Scott King Award–winning author of Twelve Rounds to Glory: The Story of Muhammad Ali, but he is also a photographer of a wide range of subjects. His photographic essay of Hughes’s “My People” exemplifies the poet’s mission of exalting the specialness of African Americans. Smith captures his models’ inherent beauty and joyful exuberance, and the sepia-toned pages evoke the pleasures of paging through a family album. With care and honor, Smith supports Hughes’s spare verse, capturing the span of life from a close-up on aging hands to the promise in a toddler’s smile.

“My People”

The night is beautiful,

So the faces of my people.

The stars are beautiful,

So the eyes of my people.

Beautiful, also, is the sun.

Beautiful, also, are the souls of my people.

Smith’s photographs are laid out carefully, pacing the poetry to allow for resonant silences between the words. “The night” opens on a double-page spread of blackness, as a man’s full lips, nose, and forehead emerge from the background: his eyes are closed and his face radiates serenity. As the page turns to reveal “Is beautiful,” a glowing smile beams and new light reflects from the man’s eyes. The joyful illustration of “So the faces” gives way to a more intimate moment as a woman and a girl gaze at one another in quiet happiness, harmonizing with the line “Of my people.”

It is almost as if in this one volume Smith is washing away centuries of negative imagery. The cartoonish nappy hair of past insults is erased as Smith’s camera closes in on the beauty of a woman’s hair, entwined with diamonds. “Beautiful, also are the souls of my people” is visualized in the soulful movement of song and dance. In a thoughtful afterword, Smith notes his choice to include only black people in the pictures, reflecting that Langston Hughes’s words do not dismiss other groups but that in “My People” he is celebrating his own.

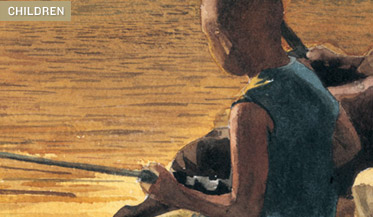

E. B. Lewis is a teacher and the acclaimed illustrator of many children’s books; his prizes also include a Caldecott Honor and a Coretta Scott King Illustrator Award. For his most recent volume, he has chosen to illustrate one of Hughes’s best-known poems, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers.” First published in The Crisis in 1921, it was collected in the poet’s first book of verse, The Weary Blues, in 1926.

I’ve known rivers:

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the

flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young.

I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep.

I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it.

I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln

went down to New Orleans, and I’ve seen its muddy

bosom turn all golden in the sunset.

I’ve known rivers:

Ancient, dusky rivers.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

(Editor’s Note: Visit the poets.org website to hear Langston Hughes talk about the genesis of the poem and read it aloud.)

Lewis’s paintings magnificently complement the text, as visual echoes of themes from the poetry create a figurative counterpoint with Hughes’s own incantatory repetitions. But it is with light that Lewis’s watercolors work their real magic. Light plays on the water and reflects off a bowed forehead; figures glow with vitality in the sun, and the dark washes of night are pierced with the white light of the sunrise on the horizon. Adding depth and sublimity is Lewis’s rich visual vocabulary of blues. He produces a steel blue that ripples on the water’s surface, and his range of sky hues swings from azure to lavender tones: we are submerged in the aqua of the Nile and the sapphire and Prussian and midnight blue water of night.

The word illuminate can mean “to make lucid or clear” but also “to make resplendent.” In both senses, Pinkney, Smith, and Lewis illuminate Hughes’s originals bringing fresh light — and a new resplendence — to works of language that were already gloriously afire.