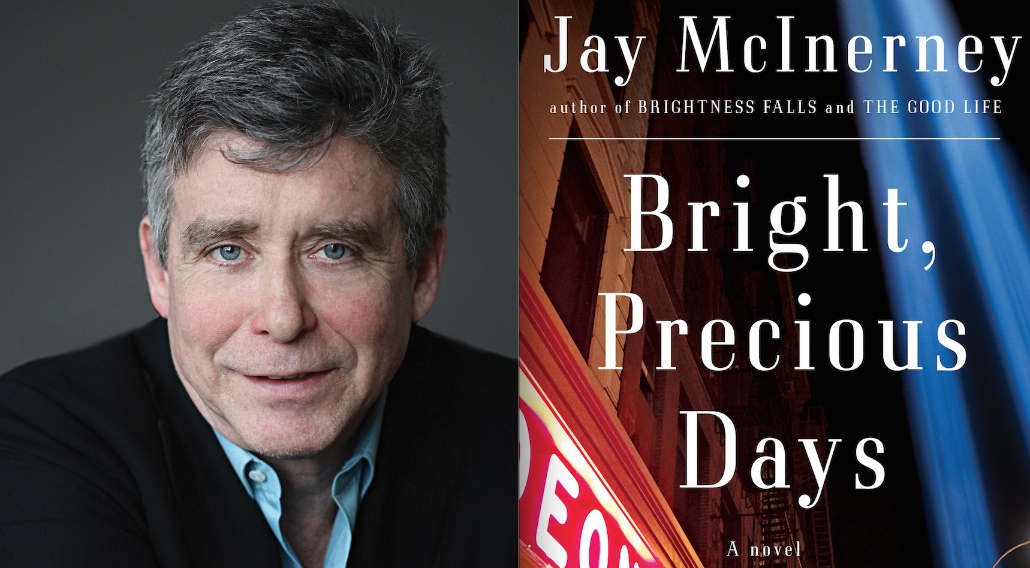

The Moth and the Flame: Jay McInerney on “Bright, Precious Days”

In deep middle age, the Russell and Corrine Calloways have passed their peak. Or at least Russell seems to feel he has. The man once described as the Scott to Corrine’s Zelda, the Nick to her Nora, now stares at infomercials on TV in the middle of the night. He snores. He is subject to 3:45 a.m. panics of despair. Could it really be that his author, Jay McInerney, has reached his sixties?

Debug Notice: No product response from API

With its wistful title, Bright, Precious Days is a continuation of Russell and Corrine Calloway’s life story, which began with 1992’s Brightness Falls and continued with 2006’s The Good Life. Like all of McInerney’s novels, it’s set in Manhattan, which seemed a good place to begin our interview. —Daniel Asa Rose

The Barnes & Noble Review: “Though the city after three decades seemed in many ways diminished from the capital of his youth, Russell Calloway had never quite fallen out of love with it, nor with his sense of his own place here. The backdrop of Manhattan, it seemed to him, gave every gesture an added grandeur, a metropolitan gravitas.” I must say, odes to New York don’t get much nicer than that. Women may come and go in your books, but the city is always there. Is it the most enduring love of your life?

Jay McInerney: The city is certainly the most enduring love of my life, and it’s been the backdrop for most of my other romances. I still get excited when I approach from the east or west and catch sight of the skyline.

BNR: The word bright consistently figures into your titles. (Bright Lights, Big City; Brightness Falls; Bright, Precious Days.) Do you mean to signal a moth-to-flame sensibility in your work?

JM: I think indeed it’s a question of moth to flame. It’s a reference of course to the city lights and the fact that my characters are drawn to them.

BNR: One thing you do particularly well is deliver pitch-perfect aperçus. “Kip believed his wealth entitled him to the truth, as if it were a commodity like any other.” Residents of the Hamptons “used this obscure term [jitney] for a public conveyance because the kind of people who could afford to live in both places either didn’t ride buses or, if forced to, would never identify them as such.” Do these come as easily as they used to? Easier?

JM: I think sometimes they come very easily and other times I have to work a bit on them. There is a certain fluency when one is in one’s twenties that perhaps fades a little with time. However, there’s a wisdom, we hope, that comes later in life. On balance it evens out.

BNR: From the get-go, you’ve brilliantly documented the glamorous-but-often-superficial life of fashionable New Yorkers. Do you think you’re chiefly a satirist or a celebrant of that world — that you’re extolling it, skewering it, or both?

JM: I think both. I think my sensibility oscillates between satire and romance but that the latter is ultimately the dominant note. Pure satire is ultimately, it seems to me, somewhat sterile. I can’t write too much about people I don’t care about.

BNR: I confess I sometimes grow impatient with your fascination for “bold-name faces”: characters dine at the sort of places “where, if you read Vanity Fair and watched Charlie Rose, you’d recognize some of the faces in the room, and if you were yourself one of those bold-name faces, you’d know everyone at the surrounding tables.” Why are your characters still so concerned with having the maître d’ know their names or the waiter, their favorite drinks? I understand it’s a way of keeping score, but why are such niceties still so gratifying to your protagonists?

JM: I was trying to enliven the hackneyed phrase: the chapter is written from Corrine’s point of view, and what she sees in the restaurant is faces, not names. I’m not particularly fascinated with boldface names, but most people on the planet seem to be, hence Access Hollywood, Page Six, TMZ, et al. In the case you cite I’m writing about a particularly celebrity-saturated, self-conscious restaurant frequented by New York media people. It’s a hothouse atmosphere — I didn’t invent it, but I’m describing that world and its obsessions.

BNR: Your protagonist quotes some lovely medieval poetry about romantic love. Do you yourself write poetry? Are you a secret romantic?

JM: I wrote poetry for many years; not so much in recent years. I’m not a secret romantic. I’m a romantic.

BNR: You write about a growing exhaustion with the “ridiculous circus” of New York social life: “the babble, the postures and gestures, the ambition and striving and yearning coiled therein . . . For a moment, he recognized how artificial it all was, but he, too, was part of it.” Yet I can’t quite see you moving to backwoods Maine. What’s the solution?

JM: Well, this opinion is Russell’s, not necessarily mine. I think as you get older the social whirl becomes less interesting. But as a novelist I remain interested in social life and all of its manifestations in Manhattan. Definitely not moving to the woods, though I do spend time in eastern Long Island writing, especially in the winter, when there are few New Yorkers around.

BNR: Toward the end of Bright, Precious Days, your protagonist wakes in a panic in the middle of the night. “It was increasingly difficult to avoid the conclusion that he was . . . a failure . . . [not] ‘beloved on the earth.’ ” Yet you wrote one of the signature books of the 1980s, which is still taught in high schools across the country. Doesn’t your continued success somewhat protect you from despair?

JM: I wish I could say success protected me from despair, but it doesn’t. Success doesn’t prevent you from waking up in the middle of the night in a panic, or worrying about mortality or the well-being of your children.

BNR: You were one of the first of your generation to be swept up into the literary pantheon: hanging with Norman Mailer, etc. Was it in any way a burden to have started with such a triumph? If you had not been tapped, would you have written different kinds of books? Would you recommend the experience to other young writers?

JM: I wouldn’t particularly recommend my kind of literary success to anyone; it was very disorienting in some ways, and perhaps I didn’t handle it as well as I might have. It was more of a surprise to me than to anyone, and there weren’t really any road maps to guide me, though in fact, talking to people like Norman Mailer, who’d gone through something similar, certainly helped. He was a great friend and mentor. Early success was the hand that was dealt me. I certainly couldn’t have predicted that success, but in the end I hope I learned from it.

With its wistful title, Bright, Precious Days is a continuation of Russell and Corrine Calloway’s life story, which began with 1992’s Brightness Falls and continued with 2006’s The Good Life. Like all of McInerney’s novels, it’s set in Manhattan, which seemed a good place to begin our interview. —Daniel Asa Rose

The Barnes & Noble Review: “Though the city after three decades seemed in many ways diminished from the capital of his youth, Russell Calloway had never quite fallen out of love with it, nor with his sense of his own place here. The backdrop of Manhattan, it seemed to him, gave every gesture an added grandeur, a metropolitan gravitas.” I must say, odes to New York don’t get much nicer than that. Women may come and go in your books, but the city is always there. Is it the most enduring love of your life?

Jay McInerney: The city is certainly the most enduring love of my life, and it’s been the backdrop for most of my other romances. I still get excited when I approach from the east or west and catch sight of the skyline.

BNR: The word bright consistently figures into your titles. (Bright Lights, Big City; Brightness Falls; Bright, Precious Days.) Do you mean to signal a moth-to-flame sensibility in your work?

JM: I think indeed it’s a question of moth to flame. It’s a reference of course to the city lights and the fact that my characters are drawn to them.

BNR: One thing you do particularly well is deliver pitch-perfect aperçus. “Kip believed his wealth entitled him to the truth, as if it were a commodity like any other.” Residents of the Hamptons “used this obscure term [jitney] for a public conveyance because the kind of people who could afford to live in both places either didn’t ride buses or, if forced to, would never identify them as such.” Do these come as easily as they used to? Easier?

JM: I think sometimes they come very easily and other times I have to work a bit on them. There is a certain fluency when one is in one’s twenties that perhaps fades a little with time. However, there’s a wisdom, we hope, that comes later in life. On balance it evens out.

BNR: From the get-go, you’ve brilliantly documented the glamorous-but-often-superficial life of fashionable New Yorkers. Do you think you’re chiefly a satirist or a celebrant of that world — that you’re extolling it, skewering it, or both?

JM: I think both. I think my sensibility oscillates between satire and romance but that the latter is ultimately the dominant note. Pure satire is ultimately, it seems to me, somewhat sterile. I can’t write too much about people I don’t care about.

BNR: I confess I sometimes grow impatient with your fascination for “bold-name faces”: characters dine at the sort of places “where, if you read Vanity Fair and watched Charlie Rose, you’d recognize some of the faces in the room, and if you were yourself one of those bold-name faces, you’d know everyone at the surrounding tables.” Why are your characters still so concerned with having the maître d’ know their names or the waiter, their favorite drinks? I understand it’s a way of keeping score, but why are such niceties still so gratifying to your protagonists?

JM: I was trying to enliven the hackneyed phrase: the chapter is written from Corrine’s point of view, and what she sees in the restaurant is faces, not names. I’m not particularly fascinated with boldface names, but most people on the planet seem to be, hence Access Hollywood, Page Six, TMZ, et al. In the case you cite I’m writing about a particularly celebrity-saturated, self-conscious restaurant frequented by New York media people. It’s a hothouse atmosphere — I didn’t invent it, but I’m describing that world and its obsessions.

BNR: Your protagonist quotes some lovely medieval poetry about romantic love. Do you yourself write poetry? Are you a secret romantic?

JM: I wrote poetry for many years; not so much in recent years. I’m not a secret romantic. I’m a romantic.

BNR: You write about a growing exhaustion with the “ridiculous circus” of New York social life: “the babble, the postures and gestures, the ambition and striving and yearning coiled therein . . . For a moment, he recognized how artificial it all was, but he, too, was part of it.” Yet I can’t quite see you moving to backwoods Maine. What’s the solution?

JM: Well, this opinion is Russell’s, not necessarily mine. I think as you get older the social whirl becomes less interesting. But as a novelist I remain interested in social life and all of its manifestations in Manhattan. Definitely not moving to the woods, though I do spend time in eastern Long Island writing, especially in the winter, when there are few New Yorkers around.

BNR: Toward the end of Bright, Precious Days, your protagonist wakes in a panic in the middle of the night. “It was increasingly difficult to avoid the conclusion that he was . . . a failure . . . [not] ‘beloved on the earth.’ ” Yet you wrote one of the signature books of the 1980s, which is still taught in high schools across the country. Doesn’t your continued success somewhat protect you from despair?

JM: I wish I could say success protected me from despair, but it doesn’t. Success doesn’t prevent you from waking up in the middle of the night in a panic, or worrying about mortality or the well-being of your children.

BNR: You were one of the first of your generation to be swept up into the literary pantheon: hanging with Norman Mailer, etc. Was it in any way a burden to have started with such a triumph? If you had not been tapped, would you have written different kinds of books? Would you recommend the experience to other young writers?

JM: I wouldn’t particularly recommend my kind of literary success to anyone; it was very disorienting in some ways, and perhaps I didn’t handle it as well as I might have. It was more of a surprise to me than to anyone, and there weren’t really any road maps to guide me, though in fact, talking to people like Norman Mailer, who’d gone through something similar, certainly helped. He was a great friend and mentor. Early success was the hand that was dealt me. I certainly couldn’t have predicted that success, but in the end I hope I learned from it.