The Sisters Brothers

The best novel I read this year is the best novel I have read in years: The Sisters Brothers by Patrick deWitt. It is so perfectly in accord with my tastes and sensibilities that it immediately took a place on my list of favorite novels — a set of twenty-five oddly assorted and constantly reshuffled works (among them novels by E. F. Benson, Sigrid Undset, Charles Portis, Dawn Powell, Flann O’Brien, and Evelyn Waugh). But I’m hardly alone – the novel was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize in Britain, and last month it won Canada’s Governor General’s Award, higher than which no book can climb in those northern parts.

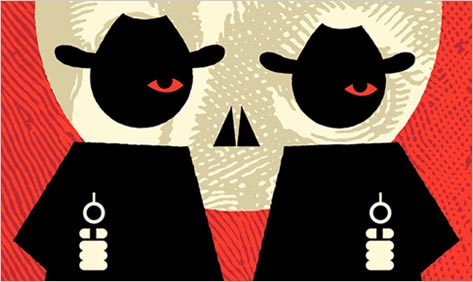

The Sisters Brothers wears the booze-and-blood-soaked mask of a western and is set during the California Gold Rush. It stars two hired killers — the brothers Charlie and Eli Sisters — and is punctuated by sixteen men shot dead, two poisoned, one drowned, and the report of another axed to death by his own hand. The death count further includes two bears, two horses, one dog, and nine beavers. Despite this carnage, the novel possesses the unlikely virtues of kindliness and understated humor, qualities that arise out of the sedate, ingenuous delivery of the story’s narrator, Eli. He is the younger though beefier brother, a gentle, homespun philosopher (and killer) whom Charlie, a domineering, conscience-free brandy bibber, treats as his stooge.

When we meet the two, they are in the employ of a man called the Commodore and are setting out from Oregon City on a mission to California to murder a prospector, Herman Kermit Warm, who has got on the wrong side of their boss. Terrible details of their last venture soon emerge, not the least of them being that their horses were burned to death. Eli has now been consigned to Tub, a “portly and low-backed” horse whom he has to beat to keep moving. (“Tub believed me cruel and thought to himself, Sad life, sad life.”)

Eli, too, is sad and profoundly lonely; his only intimate, aside from Tub — for which unhappy creature he develops a melancholy loyalty — is his brother. That relationship, despite occasional rays of amity, is not much comfort given the man’s know-it-all bossiness and predilection for drink. In a typical scene we find Charlie heading into a saloon: “He invited me along,” Eli tells us, “and though I did not much want to watch him grow hoggish with brandy I likewise did not wish to spend my time in the hotel room by myself, with its warped wallpaper, its drafts and dust and scent of previous boarders. The creak of bed springs suffering under the weight of a restless man is as lonely a sound as I know.”

Bickering incessantly, the brothers encounter a number of obstacles to their progress, including Charlie’s serial hangovers, a spider bite and tooth abscess that almost kill Eli, and problems with Tub. Early on, the poor horse is attacked by a grizzly who savages his eye; but he has a doughty heart. “Despite Tub’s eye wound he never so much as stumbled,” Eli tells us, “and I felt for the first time that we knew and understood each other; I sensed in him a desire to improve himself, which perhaps was whimsy or wishful thinking on my part, but such are the musings of the travelling man.”

The brothers ride across territory marked with occasional signs of those who have traveled before them on their own roads to ruin. A sense of desolation and abandonment pervades the land; even in the towns, disillusion and hectic desperation prevail. The Old West of The Sisters Brothers is a phantasmagorical netherworld populated by the lost and the damned: a weeping man, an abandoned boy, a witch, a terrible little girl, degraded women, mad prospectors, and bands of killers. There would seem to be something of the allegory about all this, especially as the lust for gold is the force that has given the landscape its dark glare. But the novel’s fine literary qualities operate against allegory’s oppressive portentousness and self regard: deWitt’s prose combines decorum with limberness; details of material life are vivid and concrete; and the brothers’ actual predicament, characters, and relationship with each other are central to the story and humanely developed.

Above all, the novel is very funny. Its humor is deadpan and almost ineffable at times in its adroit mismatching of elements, of good heart and dreadful deed; even its title evokes this peculiar strain of incongruity. The Sisters Brothers is a great and wonderful novel by a man still in his thirties, a writer from whom I hope we will see much more.