This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War

Social history looks at how everyday people, rather than famous political or military leaders, coped with and influenced historical events. Civil War social historian Drew Gilpin Faust, recently installed as president of Harvard University, has written an eye-opening, thoroughly researched, and highly original account of how the Civil War generation dealt with the daily, horrific realities of death.

Social history looks at how everyday people, rather than famous political or military leaders, coped with and influenced historical events. Civil War social historian Drew Gilpin Faust, recently installed as president of Harvard University, has written an eye-opening, thoroughly researched, and highly original account of how the Civil War generation dealt with the daily, horrific realities of death.

The war was supposed to be over quickly: “No one expected what the Civil War was to become,” Faust writes. “Neither side could have imagined the magnitude and length of the conflict that unfolded, nor the death tolls that proved its terrible cost.” Over 600,000 Americans would die during the war, far more than any other conflict in American history. These dead weren’t just statistics, Faust notes. “The blow that killed a soldier on the field…also sent waves of misery and desolation into a world of relatives and friends, who themselves became war’s casualties.”

Faust’s narrative is a profound examination of how soldiers and families coped with death. She describes the Christian roots of what Civil War?era Americans called “the Good Death.” The Good Death implied dying at home with family, and this Victorian concept helped ease the spiritual wounds of the living by assuring them that “the deceased had been conscious of his fate, had demonstrated willingness to accept it, had shown signs of belief in God and in his own salvation, and had left messages” for his loved ones. Needless to say, the carnage of far-off battles did much to undermine the Christian concept of the Good Death.

Yet the bereaved families wanted evidence of their deceased’s salvation. Faust shows how, after dead soldiers piled up after battles, overworked medical staffs and volunteers (including poet Walt Whitman) tried to write letters of condolence assuring families that their loved ones had died as Christians and patriots. Faust makes it clear that this work was not only overwhelming, but often impossible.

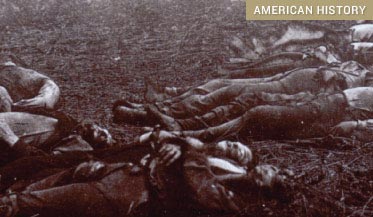

A Civil War battlefield was a nightmare of death and confusion. Neither army was prepared to deal with the mammoth job of identifying and burying so many dead, and soldiers often lay “dead or dying for hours or even days until an engagement was decided,” says Faust. Regarding the bloody battlefield at Shiloh, Union general Ulysses Grant rendered this harrowing observation: “t would have been possible to walk across the clearing, in any direction, stepping only on dead bodies without a foot touching the ground.”

Hundreds of thousands of Civil War dead were never identified, let alone given a Christian burial, so that “more than 40 percent of deceased Yankees and a far greater proportion of Confederates perished without names,” and were interred as “unknown soldiers.” The bereft families of these unidentified dead lived in constant uncertainty, harassing military and government authorities about the status of their lost loved ones.

For soldiers, the omnipresence of death numbed them. Faust shows that many soldiers even enjoyed killing, whether to avenge fallen comrades or for the perverse pleasure of it. Faust quotes a Texas officer saying, “Oh this is fun to lie here and shoot them down” and a Union officer discussing the “joy of battle.” For African-American Union soldiers, the war was especially dangerous, since Confederate troops refused to take them prisoner and executed them instead.

Burial was a massive problem. “offins were out of the question,” writes Faust, who describes the common practice of burying the dead in massive pits. Only the officers were granted a “decent” burial, creating resentment among the ranks. One Confederate soldier put it bluntly: officers “get a monument, you get a hole in the ground and no coffin.” Faust describes a whole, ghoulish industry that helped families, for a steep price, find their dead loved ones and transport their bodies back home.

The cultural impact of this harvest of death is more difficult to define, but Faust does it skillfully. She describes the elaborate Victorian process of mourning and how it dictated behavior and fashion for millions of women. Faust even shows how two deaths, that of Confederate general Stonewall Jackson and President Abraham Lincoln, became emblematic of all the deaths over the course of the Civil War.

These legions of dead created a spiritual crisis, forcing Christian believers to ask basic questions about God and justice, redemption and loss. Religion promised life after death and a reunion with loved ones in the heavenly hereafter, the author explains, but many believers sought reassurance through spiritualists who (for a fee) would contact the dead in the spirit world. Faust wonderfully demonstrates how the nation’s spiritual yearning, its sense of loss, was reflected in its literature — most famously, perhaps, in the diverse works of Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, and Herman Melville.

Some took a more jaundiced view: Ambrose Bierce, the journalist and satirist who’d been a Civil War soldier in the thick of several brutal battles, rejected the conventional Christianization of death: “It was not picturesque, it had no tender and solemn side — a dismal thing, hideous in all its manifestations and suggestions.”

It wasn’t until after the war that the federal government committed itself to locating and giving a “proper” burial to all Union dead. The system of national cemeteries was created, and the massive reburial program began. Faust explains that the Confederate dead were ignored by the federal government, triggering much resentment then (and now). “In the South,” she writes, “care for the Confederate dead…became a grassroots undertaking that mobilized the white south in ways that extended well beyond the immediate purposes of bereavement and commemoration.” Remembering the Confederate dead would become a gesture of “southern resistance to northern domination” during Reconstruction and long after.

And so the peculiar power of the Civil War’s casualties came in their massive influence on millions of families and on the nation’s future. The sacrifice, in Faust’s view, helped create an “elevated destiny” for a nation just emerging into its role on the world stage — one that would survive even the cataclysm of the 1860s and be in a sense reborn as a global force. As Lincoln said just before his own death, the national sin of slavery could only be purged in the blood of its brave youth. That horrific bloodletting would scar this nation’s psyche for generations to come.